Netflix's MH370 Documentary Is Stunningly Irresponsible

-

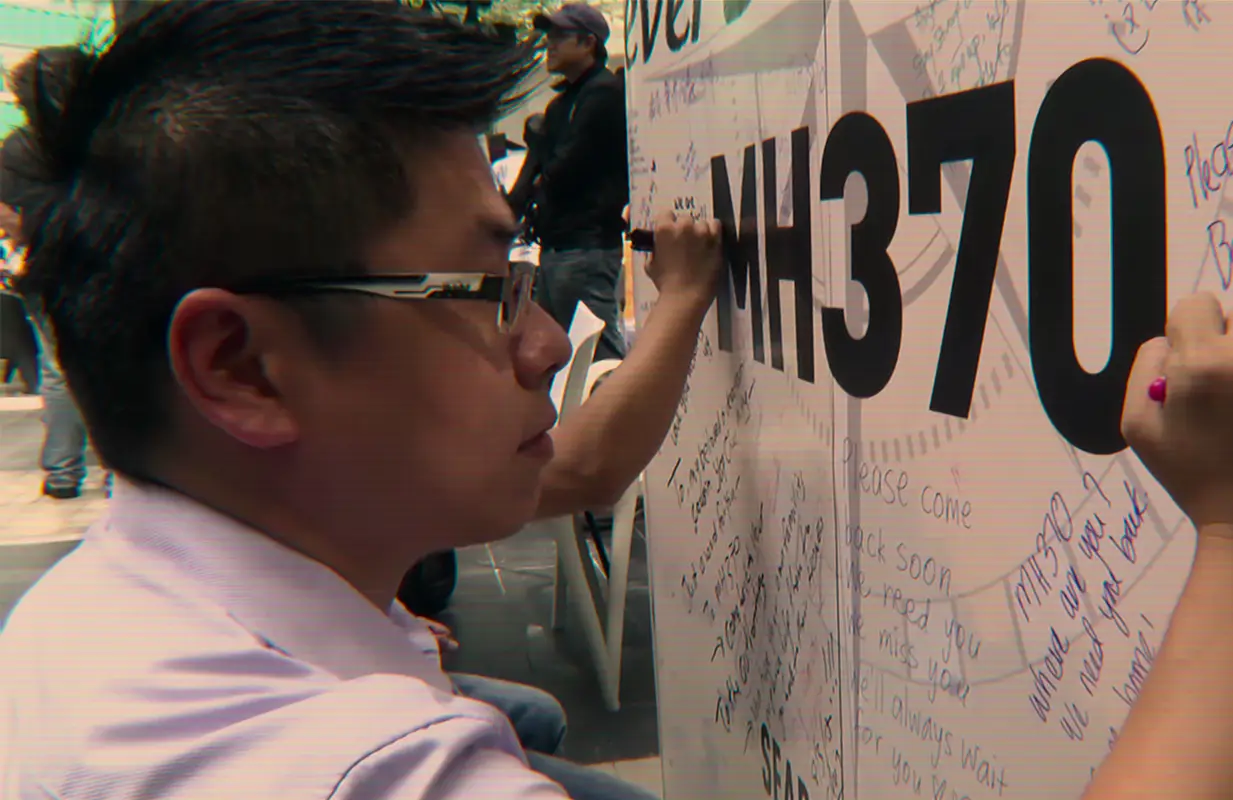

A man pays tribute to the victims of Malaysia Airlines Flight 370. (Photo: Netflix)

A man pays tribute to the victims of Malaysia Airlines Flight 370. (Photo: Netflix)The spirit of “just asking questions” pervades Netflix’s MH370: The Plane That Disappeared, a three-part documentary series about Malaysia Airlines Flight 370. On March 8, 2014, the Boeing 777 bound for Beijing disappeared from radar without warning, never to be seen again. In the almost-decade since, precious little information has emerged about MH370, and theories about everything from the plane’s trajectory to the discovery of debris in the western Indian Ocean have emerged to fill the void. The Plane That Disappeared doesn’t claim to provide any concrete answers — there’s a reason this is considered aviation’s greatest mystery — but it does question the “official narrative” by putting forth nefarious conspiracy theories about MH370 and those tasked with investigating its disappearance.

While there are multiple conspiracy theories thrown out in each episode, The Plane That Disappeared homes in on three specific ones. In Episode 1, “The Pilot,” aviation journalist (a descriptor that should be taken with a grain of salt) Jeff Wise lays out the first theory, one that emerged in the immediate aftermath of the plane’s disappearance: Captain Zaharie Ahmad Shah rerouted the plane into the southern Indian Ocean as part of a plan to commit mass murder-suicide. Wise claims “the overwhelming body of evidence pointed strongly to [this] theory,” but offers no actual data beyond a claim that the pilot’s decades of experience meant he “would know all the angles” and therefore “be able to conceive of something as complicated as this.”

Even more irresponsibly, the docuseries offers a lengthy reenactment of this theory, which Wise describes as “a final, decisive picture of what happened that night.” A dramatization shows Shah locking his co-pilot out of the cockpit, cutting the plane’s communication systems, and depressurizing the cabin, killing the 227 passengers and 11 other crew members on board. Six hours later, when the plane runs out of fuel, Wise posits, “He pushes the nose down, and he starts to slide into a dive.” It’s unlikely that we’ll ever know exactly what happened aboard MH370, but without any evidence, this scenario is pure fantasy. Propagating it on Netflix, a streaming service with 231 million global subscribers, in such dramatic fashion threatens to do irrevocable harm to Shah’s loved ones, not to mention muddy the waters surrounding the case.

In perhaps its lone moment of thoughtfulness, The Plane That Disappeared ultimately backs away from this theory and exonerates Shah. The final episode swiftly discards a revelation that Shah flew a similar route to MH370’s on the flight simulator in his basement. (Wise explains the pilot moved his cursor into the southern Indian Ocean on a map, but didn’t actually fly there on the simulator.) Later, some of the victims’ family members acknowledge that the only conclusion that has been drawn from the investigation is that “it wasn’t the pilot.” Adds Intan Othman, the wife of a flight attendant on the plane, “The only good thing that happened was that they stopped accusing Captain Zaharie of bringing down MH370.”

The other two conspiracy theories featured prominently in the docuseries aren’t handled with nearly as much care. Episode 2, “The Hijack,” calls into question Inmarsat satellite data — the only data set to offer a somewhat-clear picture of the plane’s trajectory after its communications went down — that found MH370 headed south into the Indian Ocean after turning back over the Malay Peninsula. For months, crews scouring the area were unable to locate any debris from the plane, prompting some to ask whether MH370 could have actually turned north. Wise explains that he once held the Inmarsat data in high regard, but “the entire tenor of the subject” changed when he learned the connection to the company’s satellite “came back to life” after other communication lines were cut.

Between his Inmarsat doubts and the downing of Malaysia Airlines Flight 17, which was shot down by Russian forces on July 17, 2014, Wise came to conclude that the Russians were involved in MH370’s disappearance, as well. Once again, the docuseries gives him free rein to lay out a convoluted theory involving “three ethnically Russian men on board the plane” who snuck into the electronics bay, took control of the plane’s computer system, altered the Inmarsat data, and then flew north, crashing into the desert of central Kazakhstan.

Wise believes this was done to shift attention away from Russia’s invasion of Crimea, but while this is certainly a tactic in Vladimir Putin’s playbook, it’s not exactly sound logical thinking. As his naysayers, including Inmarsat’s Mark Dickinson and Malaysia Airlines crisis director Fuad Sharuji, explain in the closing minutes of the episode, Inmarsat doesn’t typically use its satellite information to track planes, so it’s unlikely that hijackers would know to mess with it, in the first place. Furthermore, says Sharuji, “It is impossible to fly the aircraft from the avionics compartment,” a statement that invalidates Wise’s entire theory.

And yet, despite this seemingly-objective piece of information, director Louise Malkinson and producer Harry Hewland still allow Wise to have the final word. He argues that because part of his theory — the idea that someone could turn off the plane’s electronics from inside a compartment located near the cockpit — is possible, it’s unfair to lump him in with “the Loch Ness Monster and Bigfoot.” There’s no acknowledgement that Wise’s version of events is as thinly-sourced as those folk tales, just a moment of gaslighting that encourages viewers to ignore their better judgment and accept his half-baked theory as truth.

But by far the most outlandish, far-reaching conspiracy theory comes in Episode 3, “The Intercept,” in which French journalist (again, be wary of that term) Florence de Changy details a global cover-up orchestrated by the U.S. government. De Changy, too, grounds her work in the supposition that radar data was “fabricated” to make it look like MH370 U-turned over the Malay Peninsula. The docuseries holds up the discovery of citizen detective Cyndi Hendry as evidence that the plane continued on its path towards Beijing after it lost contact with air traffic control. Hendry claims to have found satellite images of debris in the South China Sea, but when she compares them to photos of the plane, the images are far too blurry to show anything conclusive. (Fittingly, Hendry’s satellite images look more like Rorschach tests than identifiable plane parts.)

An analysis of the plane’s cargo yields another nugget for de Changy to latch onto: MH370 was supposedly carrying 2,500 kg of electronics that were delivered under escort and loaded onto the plane without having been scanned by X-ray machines. The airline’s records describe these electronics as lithium ion batteries and walkie-talkie accessories, but de Changy, without offering any additional support for this claim, suggests these gadgets could have been “highly sensitive U.S. technology” that China illicitly obtained.

A third reenactment brings her baseless hypothesis to life. As MH370 leaves Malaysian airspace, it’s intercepted by American AWACS (Airborne Warning & Control Systems) aircraft, which jam the passenger jet’s communication systems and cause it to disappear from radar. De Changy posits that the AWACS ordered Shah to land the plane, and when he refused to alter his route, the United States took drastic measures “to stop the plane and its precious cargo from arriving in Beijing,” either through a “missile strike, or a midair collision.”

As with Wise’s hijacking theory, The Plane That Disappeared offers a half-hearted cross-examination of de Changy’s notion. Blaine Gibson, who has found various plane parts confirmed to have come from MH370, insists de Changy’s claim “denies all the evidence that there is,” like the Inmarsat data and the U-turn discovered by the Malaysian military, and would require a half-dozen countries to collaborate on a massive conspiracy. But by this point, Gibson’s credibility has already been called into question by Wise, who accuses him of working with the Russians to mislead the public about the plane’s trajectory. (Gibson says this is “patently ridiculous” and “very serious defamation.”) If the docuseries were truly interested in challenging de Changy’s theory — or any of the conspiracies presented throughout its three episodes — surely it would find someone more qualified, or someone who has kept enough distance so as to offer an objective analysis, to deliver a rebuttal.

This proves to be the ultimate problem with MH370: The Plane That Disappeared. Malkinson and Hewland don’t seem to have considered evaluating the tragedy from a responsible perspective, or even a human one — the families of the victims are interviewed, but they’re almost exclusively asked about the investigation, not their loved ones. With so little information available about the incident nearly a decade later, maybe there’s no way to discuss MH370 without devolving into conspiracy theories. But it would have been nice to see Netflix try a different approach, perhaps one that shields it from a defamation lawsuit.

MH370: The Plane That Disappeared is now streaming on Netflix. Join the discussion about the show in our forums.

Claire Spellberg Lustig is the Senior Editor at Primetimer and a scholar of The View. Follow her on Twitter at @c_spellberg.

TOPICS: MH370: The Plane That Disappeared, Netflix, Malaysia Airlines Flight 370