The Ending of The Last of Us Didn't Hit as Hard on HBO

-

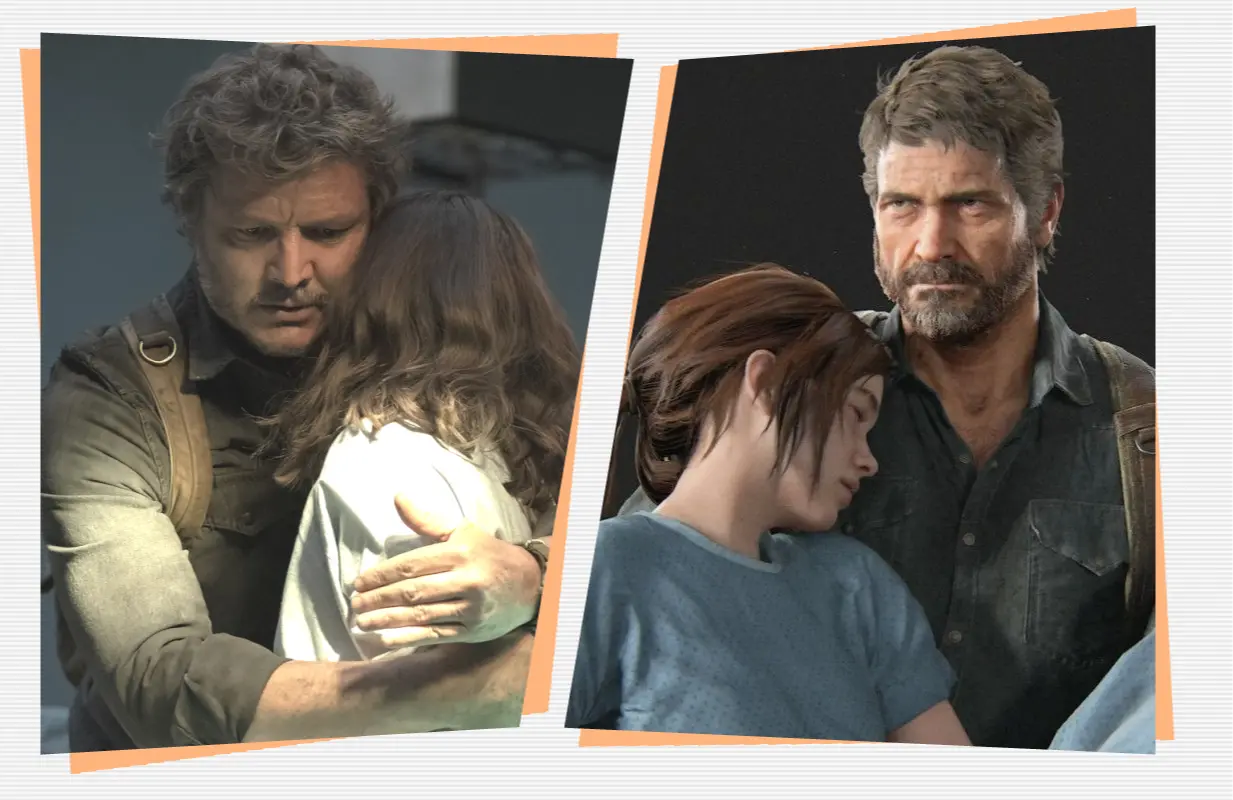

Left: Pedro Pascal and Bella Ramsey in The Last of Us (Photo: Liane Hentscher/HBO). Right: Screencap from The Last of Us game.

Left: Pedro Pascal and Bella Ramsey in The Last of Us (Photo: Liane Hentscher/HBO). Right: Screencap from The Last of Us game.A world destroyed by a virus that turns people into undead creatures. A weathered survivor making his way across the aftermath. A lone child considered humanity's final hope. We're talking, of course, about The Walking Dead: Daryl Dixon, which wrapped up its first season last night on AMC. You almost have to feel sorry for the show. Because no matter how well fans responded to the ongoing adventures of Norman Reedus' post-apocalyptic outlaw, his solo spin-off plainly sits in the shadow of a different Sunday night sensation that premiered in 2023. And no matter how well Daryl Dixon closed the book on its first chapter, it's unlikely to inspire a fraction of the conversation the world has devoted to the ending of The Last of Us.

Is a spoiler warning even necessary? Who would it benefit at this point? Nine months after HBO's huge hit premiered to glowing reviews and big ratings, there may not be a lonely soul left on the web who doesn't know how the cross-country voyage of Joel and Ellie concludes. People have been talking about the ending of The Last of Us for a lot longer. After all, it was ported faithfully from the source material, the Playstation stealth-action milestone that turned 10 in June. It's fair to say that plenty of the acclaim the game has earned over the years rests on its closing minutes. When people cite The Last of Us as a high-water mark for video-game storytelling, they're definitely factoring in the ending, if not building their whole argument around it.

Everyone involved in the show knew better than to mess with success. The season ends almost exactly as the game did: with hardened smuggler Joel (Pedro Pascal) and his immune, adolescent charge, Ellie (Bella Ramsey), finally reaching the hospital in Salt Lake City, where the militant group the Fireflies hope to find a cure for the fungal virus that's turned the species into clicking mushroom zombies. But Joel can't accept the fatal medical procedure on which that hope hinges. And so he turns his protective fury on the whole operation, cutting a horrible path through the Fireflies, and then "saving" Ellie from the chief surgeon — an act of cold-blooded murder that effectively dooms humanity's chances of long-term survival.

Again, that's all there in HBO's adaptation, which follows the game's conclusion to the letter. Yet reproducing a story beat for beat isn't the same thing as replicating its power. On TV, that famous ending doesn't have the same impact — in part because of subtle but significant changes made en route to it, but also via the translation from one medium to another. The showrunners of The Last of Us — including Neil Druckmann, who wrote and directed the game and its ambitious sequel — preserved the exact nature of what happens but not how we experience it.

Now, as ever, there's a Rorschach quality to the ending. The more charitable (or merely sentimental) might read it as the culmination of a recovery drama: By saving his surrogate daughter, Joel is able to finally let go of the real daughter he couldn't save 20 years earlier — the formative loss that kicks off both the game and this first season of television. Surrogate, though, might be the operative word here. The darker, more persuasive read on the closing minutes of The Last of Us is that this broken man has made Ellie a living proxy for everything he's lost. His love for her is indistinguishable from his trauma. Ellie's wishes, the fate of the world — none of it matters to Joel. He becomes a terrible force of single-minded paternal rage, a monster channeling his unprocessed grief into violence.

Watching the show, it's perhaps easier to leave with the less withering interpretation. In general, The Last of Us has been slightly softened for TV, even as its creative team fought to preserve some of its bleaker elements (including the events of the original ending). The most obvious example of the series brightening its corners is the widely (though not universally) acclaimed third episode, an extended flashback that expands upon a relationship only described in the game, turning a curdled romance of probable convenience into a doomsday love story for the ages.

Less dramatically has Joel and Ellie's bond been shifted, or at least accelerated. If the arc of The Last of Us is Joel letting down his defenses and growing to really care about someone again — or maybe simply undergoing a gradual emotional transference, applying all his dormant feelings for his daughter to Ellie — the game smartly slow-plays it. In the show, it's clear much earlier that Joel is becoming attached. Maybe that's Pascal, who can't help but betray instant cracks in Joel's protective emotional armor; we see flickers of warmth from him almost immediately. It could also be one of many ways that moving The Last of Us out of its original medium alters its effect. It's much easier to detect the blossoming of affections in a character when you're looking at their face instead of the back of their head.

Either way, speeding up Joel's thaw isn't necessarily a welcome liberty to take with this story. It makes it easier to read The Last of Us in more sentimental terms, as the touching father-daughter drama the game arguably subverts and only pretends to offer. The ending plays differently, maybe less ambiguously when the bond between these characters seems rock-solid by Episode 4.

The show also pulls back significantly on the violence of the game. It's very much a prestige-TV version of The Last of Us — more scenes of Joel and Ellie having serious conversations in cars, fewer scenes of them evading or battling waves of armed strangers. It makes some sense that Druckmann would reconfigure the ratio of action to drama in retelling his acclaimed epic: What's fun to play isn't necessarily fun to watch ad nauseam, though all the fallen-world brooding looks a little more Walking Dead generic when not ballasted by intense stealth combat.

The real issue here is that we need to see Joel kill a lot of people. The violence is not pointless. It's instrumental to the larger moral architecture of The Last of Us. So much of the story is about the allowances we'll make for the character because he's on a righteous quest. The stakes are clear: He's not just defending himself and a child from murderers and rapists. He's trying to save all of humanity. If that's the end, doesn't it justify almost any means? Joel's brutality looks virtuous throughout.

Until he kills the doctor. That renders all his bloodshed meaningless. Or rather, it gives it exactly one meaning — personal, compulsive, obsessive. The body count Joel racks up on the way to Salt Lake City has to be massive. We need to see Joel viciously annihilate the "right" people before he annihilates the wrong ones. We have to see how all that death was essentially for nothing. Scaling back the carnage doesn't just make our main character easier to root for, more heroic and sympathetic. It also deprives The Last of Us of the damning dichotomy of its ending — the way his final rampage looks all the more disturbing as a mirror of what he's been doing all along.

Or what we've been doing. Maybe the true power of The Last of Us has always been inextricable from its interactive complicity — from how it implicates the player in its design. All video game adaptations run into this problem, as no great game is just great because of the story it tells. Gameplay is crucial even to a game as famously cinematic, novelistic, and narratively driven as The Last of Us. In fact, Druckmann used the player to make a larger point about the nature of choice, in part by actually limiting the interactivity in a crucial way.

One criticism sometimes lobbed at the game is that it's ruthlessly linear: In an age of sandbox experiences, it denies players any say in how the story ultimately plays out. But that's a feature, not a bug. Choice is an illusion in The Last of Us. We can control how we clear a room of enemies, how we survive one brutal encounter to get to the next. But the path of the story will always be the same. The outcome will never change. That's the game making a rather rueful point about trauma. In a sense, Joel's life can only go in one direction, to one destination. He's no more in control of the narrative than we are. His loss has sealed his fate.

The cruel genius of The Last of Us as a gaming experience is that you get to that makeshift operating theater and you have to kill the doctor. The game allows no other choice, no choice period. Making the player press that scalpel into the innocent man could be seen as an act of hectoring sadism. (Certainly the sequel only ramps up the guilt-tripping aspects of the original — that familiar revenge-movie tactic of placing some blame for the violence on the audience being encouraged to enjoy it.) But limiting our choice as a player also functions as a medium-specific expression of the story's bracing pessimism, its assertion that trauma can flatten life's winding path into a road as straightforward and unwavering as a video-game level.

It's an aspect of The Last of Us impossible to cart over to TV. And so the ending just doesn't hit as hard. It can't. Of course, those who experienced the story only through this year's small-screen adaptation wouldn't know what they're missing… just as those who played the game couldn't hope to experience its final plot turn with fresh eyes. Like Joel, dyed-in-the-wool Last of Us fans are trapped by the design of the past, all 0f our reactions determined by what we've already experienced.

A.A. Dowd is a writer and editor who lives in Chicago.

TOPICS: The Last of Us, HBO, The Walking Dead: Daryl Dixon, Bella Ramsey, Craig Mazin, Neil Druckmann, Pedro Pascal

- The Last of Us season 3 confirms release window, but unfortunately it's likely going to be the last chapter

- The Last of Us season 2 episode 6 preview teases that it isn't last of Joel yet

- The Last of Us season 2 episode 5 reveals an airborne threat more chilling than infected bites

- The Last of Us loses viewers following the major character death of Joel in Season 2