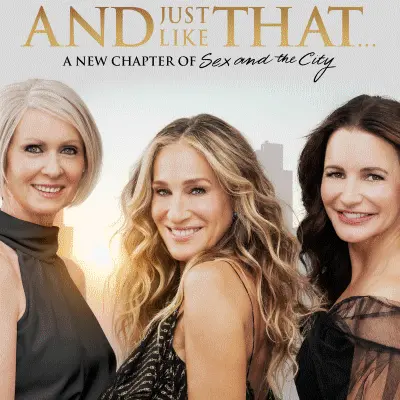

And Just Like That was funny, cringey, sweet and uneven—which means that it's pretty much as delightful as the original

-

"It was a bit jarring to be thrust back into the world of Carrie, Charlotte, Miranda, and Samantha," says Gabrielle Bruney. "(Samantha may have been absent, but it’s her world too, nonetheless.) After a decade filled with gray movies and minimalist interiors, and sitcoms that either had no jokes—most of them—or absolutely perfect jokes—a blessed few—it felt almost dislocating to return to Sex and the City’s technicolor realm of escapist good cheer and sometimes-funny-sometimes-cheeseball humor. It didn’t help that the long awaited reboot landed with a bit of a thud when it debuted in December. Reviews were mixed, and Big’s death by Peloton in the premier felt like a lame stunt, before the rape accusations against actor Chris Noth turned it into a very depressing stunt. There were some bumpy early episodes, with the sense that the team was back in the saddle, but not yet in full control of the horse. Having ridden out the full season, I’ve got to admit it: I thoroughly enjoyed And Just Like That. In the years leading up to the show’s debut, there was a lot of talk about whether a series about four rich white women could feel relevant today, which has always struck me as funny for its implication that the lives of rich white women held some sort of universal resonance in 1998. (They did not!) Still, I loved the series when I was growing up, viewing it in family-friendly syndication on TBS. The movies burned through a bit of my SATC goodwill, but I never felt that the show, which would be ridiculous no matter when it took place, was uniquely unsuitable for the contemporary media landscape. SATC created and inhabited its own fantasy bubble, and AJLT succeeds because it expands that bubble, but doesn’t burst it."

ALSO:

- And Just Like That had a weird pull with some watching new episodes as they dropped in the middle of the night: "I’m not sure any show in recent memory has inspired a stranger response in audiences and critics than And Just Like That… since it premiered in December," says Heather Schwedel. "At first, all anyone could talk about was how bad the Sex and the City reboot was. What were they doing to Miranda? And how could they write off Samantha like that? And oh my God, that death scene. It was bad, but it was also, maybe, compulsively watchable. And so even as they trashed the show, people kept watching. You could call that a guilty pleasure, but at what point does guilty pleasure slide into pleasure, full stop? As the weeks went on, some critics wrote rousing defenses of the show, Che Diaz discourse flew fast and furious, and former Jezebel staffers owned up to being so obsessed with the show that they up and started an extremely funny limited-run Substack about it. But the strongest evidence of AJLT’s weird pull on audiences to my mind was a viewing habit I noticed people adopting around it that I’ve never seen before: New episodes went up on Thursdays at 3 a.m. Eastern time, and a certain segment of viewers weren’t waiting until typical leisure screen time hours, the evening, to watch—they were finding pockets to watch during the day Thursday, whether over a snack or an afternoon break. Some were even waking up early to fit in their weekly session of exasperated but deeply affectionate eye-rolling. From personal experience, I can tell you that more than once I found myself awake at 2 a.m., usually around when I go to bed, wondering if I should try to stay up another hour for that week’s episode to go up and then another half hour to 40 minutes to watch it, because, well, I wanted that dopamine hit and I didn’t want to wait another 16 hours for it. Now, I’m not saying everyone was doing this. Much like Carrie Bradshaw, I only talk to about three people regularly, so I can’t speak for the viewing habits of the masses. But I had a hunch, I’d heard a few similar anecdotes from acquaintances, and I have social media, where I clocked many examples of people watching And Just Like That at pretty odd hours."

- And Just Like That's season finale was shockingly beautiful after a frustrating season: "As a nation today, in a rare and beautiful moment that could prove to be historic, we do agree: Sarah Jessica Parker’s performance is as charismatic and magnetic as it’s ever been—a singular gift to television—and the elegant handling of Carrie Bradshaw’s story arc this season has been And Just Like That…’s beautiful saving grace," says Kevin Fallon. "HBO Max’s gambit on following Carrie and her girlfriends as women in their fifties—controversially but unavoidably without Kim Cattrall’s Samantha—has turned the water cooler into a flaming bonfire of discourse. Extreme opinions about the show and its characters have been preached with the ferocious conviction of a radical at a pulpit. Sex and the City is a religion, and anything that goes against the Word of God—cherished memories of Carrie’s puns—is akin to sacrilege. But that’s been the somewhat surprising revelation of these last weeks spent watching and debating And Just Like That… It’s a weekly gathering akin to church. For as much backlash as there was to some of the early episodes, and certainly to some specific character additions and plot decisions (why you gotta do my man Steve like that?), everyone watched it. Each week we gathered. We bore witness. We communed. We complained. Maybe there were some (many) among us who, perhaps like church, viewed it as an obligation—the spiritual version of a 'hate-watch.' But then, as we considered the gospel we just heard and worked through our feelings about it with our friends (and the internet), we experienced something. I couldn’t help but wonder… was it enlightenment?"

- And Just Like That had the opposite message of Sex and the City -- "We can’t have it all, actually": "Sex and the City, which ended in 2004, convinced us that women could have it all: orgasms, love, money, babies, careers, shoes, mortgages, marriage and all the fabulous escapism you could possibly want," says Robyn Bahr. "And Just Like That rewrites that conclusion with a little more earthbound sagacity this time. We can’t have it all, actually. We can’t just settle into listless partnership until we croak. We can’t expect our kids to remain malleable for the rest of their lives. We can’t assume our partners will live forever. And, perhaps most importantly, we can’t lean on our cliques indefinitely. Sisterhood doesn’t always have to be sacrosanct. There are innumerable reasons to lovingly hate-watch this series, from its try-hard cultural tone deafness to its superfluous vision of carefree mega-wealth to its insistence that insufferable Che Diaz is the funniest and most famous comedian in the world. Still, I genuinely looked forward to it every week. Call me a classic Charlotte, but I prefer to see the emotional intelligence hidden underneath all its impossible dumbness. Perhaps we’ll all judge these characters way less, however, when we stop seeing them as sublimating our own identities."

- And Just Like That tried addressing too many criticisms of Sex and the City: "And in each case, it didn’t really do any justice to itself or the actual realities of our culture today," says Erin Evans. "Yes, Sex and the City lacked diversity; no, I don’t want to see a bunch of sidekicks of color. Yes, I want to see queer relationships on TV; but um, 'Hey, it’s Che Diaz' seemed like such a caricature in much of the series. The show was just giving #TeamTooMuch way too much of the time, and then it wasn’t funny or sexy on top of that. Ugh. And then, I mean, the biggest trivial thing for me was that the gray wig they put Miranda in got worse and worse with every episode. I think there was one scene in the first episode where her hair looked GORGEOUS, and then they slapped that $10 beauty supply store wig on her and said: 'Good luck to you, lady who we do not actually know any more.'" Evans adds: "Oh AND around the characters aging: It definitely seemed like the only way the writers knew how to talk about it was making fun of them getting older. Hated it! I mean, we all love a good $10 beauty supply store wig when we need it, but on national television? With an HBO budget? Stop the madness."

- And Just Like That was over before it even started: "Executive producer Michael Patrick King, who has long been the keeper of the franchise created by Darren Starr, and whose other TV projects include 2 Broke Girls and The Comeback, excels most at putting bon mots in the mouths of over-the-top female characters," says Judy Berman. "Carrie’s mourning took King out of his comfort zone, not only slowing the pace of a narrative that had always been defined by the kinetic motion of city life, but also introducing an element of tragedy that never quite meshed with the more familiar, breezier story lines. I mean, were we supposed to laugh or cry when Miranda’s first hookup with Carrie’s nonbinary podcast boss left a convalescent Carrie to soak her bed in pee? Because I just felt deeply uncomfortable. The other women’s arcs were, somehow, worse. Formerly a sweet-natured priss, Charlotte devolved into the worst kind of helicopter parent, micromanaging every element of her children’s lives while still finding bandwidth to judge her friends’ choices. (No wonder Lily can’t even insert a tampon independently!) Poor Miranda kicked off the season ready to reeducate herself for a second career in public-interest law, only to Karen her way through Columbia and, ultimately, blow up her life in New York to follow her new love Che Diaz’s bliss to California. She and Steve never seemed like a great match, it’s true, but suddenly her family, her political convictions, and her career no longer mean anything to her? That’s not the Miranda we know. Meanwhile, the reduction of Samantha’s presence to a series of terse text messages with Carrie made a franchise notable mostly for its blunt depictions of women’s sexuality seem weirdly prudish."

- And Just Like That set itself up to fail by being afraid of its own nostalgia: "Sex and the City was not only defined by what now plays as unseemly opulence, but a particular brand of white feminism that could be read as progressive at the time, but not always, and less and less as time progressed," says Soraya Roberts. "In its attempt to atone for Sex and the City’s now glaring sins, And Just Like That… replaces much of what also made the show so seductive with cloying gestures that misunderstand the present and utterly fail to redeem the past. While I was never much of a fan of Sex and the City, when I moved to New York a decade after first seeing it, I couldn’t help but have those four women on my mind. And because their fantasy life had become mine by cultural osmosis, I felt the same sense of betrayal that a lot of women probably did when reality did not match in the end. Perhaps the impulse to watch And Just Like That… is the same impulse I felt to think of Sex and the City all those years ago—it is nostalgia for the aspiration of my youth, before mature reality had hit. And Just Like That… offers only further betrayal: the sanitization of an outdated fantasy. That is to say, not only do women my age have to live with the repercussions of our past actions, And Just Like That… also subjects our past dreams to retroactive correction."

- And Just Like That's season finale was as underwhelming as the rest of the series: "I can see why Michael Patrick King et al. would want to do a better job than they did on this season, which leaves us as a chronicle of failed opportunities for these beloved characters," says Gwen Ihnat. "But these 10 episodes don’t really bode well for the show’s future, sorry to say. Let’s face it; without Samantha, the show doesn’t really work."

- What’s bizarre about And Just Like That is that Sex and the City has always been about difficult conversations: "Carrie, Samantha, Charlotte and Miranda regularly critiqued one another’s romantic choices, discussed their partners and admonished each other when they needed to be admonished," says Adam White. "Miranda was open about disliking Big; Charlotte and Miranda were furious with Carrie for cheating on Aidan; Carrie told Samantha that her sexual frankness made her uncomfortable. There was a level of honesty to their individual dynamics that felt real and believable: friends so at ease with each other that they could verbalise the typically unspoken. All of that has been absent from And Just Like That, and replaced with an odd – and ethically dubious – paean to objectivism. Couple that with the endless hectoring from Che about the importance of 'living your truth,' and the show seems to suggest that achieving personal happiness is the ultimate goal, regardless of whether others are harmed in the process. Similarly, characters have repeatedly reprimanded each other for 'judging' people’s choices, as if maturity equals a kind of quiet indifference. But it’s a strangely cold message to push, as if growth can only arrive by divorcing yourself from opinions or friendly concern."

- Being obsessed with the frustrating And Just Like That was more than hate-watching: "For a show I didn’t particularly like, And Just Like That has consumed an inordinate amount of my mental energy for the last two months," says Meredith Blake. "I’ve discussed it on social media, with other moms at drop-off, and in group chats with friends who, like me, wondered why Charlotte’s daughter had such trouble inserting a tampon and couldn’t wait to see which of Carrie’s exes would show up in a surprise twist (sadly, none of them). And it wasn’t as simple as hate-watching, where a show is so viscerally awful it feels cathartic to dump on it collectively. It was more like King had taken us all hostage and we’d developed Stockholm syndrome. At some point it became clear that the audience cared more about these characters — and certainly understood them better — than their own creator did."

- One of the most disorienting features of And Just Like That was its absolutely baffling negotiation of time: "Maybe this had to do with the episodes being longer than the original series, which were tight half-hours spent zipping between the four women, their stories at various degrees of gravity or absurdity but connected by Carrie's voiceover, always pondering a new question about sex, the city, what have you," says Mary Sollosi. "But now there are no unifying episode questions (only cutesy closers) and no clear timeframe for when anything took place. Episodes felt lingering, but storylines that needed more attention seemingly vanished into thin air (promptly dropping alcoholism???). Don't get me started on the show's maddening use of ellipsis, cruelly deployed when our heroines have meet-ups in the glamorous foreign metropolises of Paris, France, and Cleveland, Ohio. We realize in the finale that the whole season took place over the course of one year, and I can't begin to guess how much of that time was just the seasons-changing montage while Carrie wrote her grief memoir and how much of it was the actual action of And Just Like That, so wonky was the pacing. This show had a rhythm that nobody could dance to."

- Here are the winners and losers of And Just Like That Season 1

- And Just Like That's writers weigh in on Season 1, from Miranda to Steve to Che

- Sarita Choudhury enjoyed the extreme reactions to And Just Like That: "When I was reading the script, I didn’t feel any of that pressure, but I know while watching it now that has come up," she says. "I’m not a worrier, though. I know it’s weird to say. People are writing so much about the show that if I was a worrier, I would have to give that up immediately. You have to have fun with all this and accept everyone’s going to have opinions. I find all of it refreshing, the amount people are talking about it, even though I know not all of it is good. It makes me happy people are watching. I usually don’t read reviews because I’m so vulnerable. With this, I do try not to read, and it’s hard because the headlines are everywhere. Sometimes I do, and I laugh out loud. It feels like a sport and I’m in the Colosseum or something. Maybe because it’s so extreme, I feel less vulnerable. Every week I was just expecting more and more."

- And Just Like That creator Michael Patrick King admits "we took the viewers through a lot": “A lot of people reacted like it was quite an aggressive loofah shower of emotion. It was good for them, but it hurt!” says King. And Just Like That writer Julie Rottenberg adds: “To have such an incredibly engaged fan base, where they care so deeply about these characters as if they are real people, that’s something that’s hard to achieve. So we take the passion and even the rage — we take that as a sign that we’ve done something right.”

- Why was Aidan absent after John Corbett said he'd be back?: As writer Julie Rottenberg notes, "John Corbett should be writing personal apology notes. We didn’t say anything." Asked if Aidan and Carrie are old news, King responds: "No, there’s nothing old news about Sarah Jessica Parker and John Corbett as actors and beings and interests. The fact of the matter is, we never said anything about Aidan, just like we never said, Steve and Carrie or getting together. We always try to be very restrained and look at the reality of what people are experiencing and it has nothing to do with Aidan coming or not coming. It really just felt like this was a lot for Carrie. This season was a lot. We wanted to get her through this and into the light—the last episode is called, 'Seeing the Light.' We wanted to get her out. (Aidan’s return) is a big storyline that everybody at home wrote that we had never intended."

- King points out Sex and the City characters started out simpler than they ended: "I will start with a reaction that people said to me before it was even on — just when it was announced — and that was, 'Oh, I can’t wait to have a cosmo and sit back and see my girls,'" he says. "I thought, 'Oh, well, we’re not doing that.' I mean, deliberately, there’s not even a cosmo in the show until episode four at the bar with Seema, where Carrie is trying to be in that other show before death. Miranda says to her that it’s fun. There’s no death. She didn’t know Big. She’s having a suspended reality in the old show by having a cosmo and talking about dating apps. So to me, I knew that we were always going to broaden the characters the way we did over the six years and two movies. Those characters in Sex and the City started out simpler than they ended. They started as archetypes and became fully fleshed-out characters. They started as 'I got to get a man' and wound up being, 'I’ve got to love myself and see what the universe hands out to me.' So for us to simplify 20 years later, when the world is incredibly more complex, would be a mistake. The other thing that Sex and the City did, where I felt we were comfortable, was that we commented on what people were talking about and experiencing in society when they were 35 and single. We knew our template was to comment on where they are, where society is, at this age, at this point in New York, and to try to bring in as much of the world and create a slight overview rather than be in it. I feel we accomplished what we wanted to accomplish, which was to show a new chapter in this show called And Just Like That. Also, you’ve only seen 10 episodes of this. You’ve seen six seasons and two movies of the other characters. To put the scale out and say, “Oh, well, I don’t know them as much” — of course. You’ve known Miranda 20 years. You’ve known Nya for 20 minutes."

- Sarah Jessica Parker wouldn't be okay with Kim Cattrall joining And Just Like That: “I don’t think I would, because I think there’s just too much public history of feelings on her part that she’s shared,” Parker tells Variety. “I haven’t participated in or read articles, although people are inclined to let me know.” Parker and King are on the same page on the matter. “We didn’t go to Kim for this, you know,” Parker says. “After we didn’t do the movie and the studio couldn’t meet what she wanted to do, we have to hear her and listen to her and what was important to her. It didn’t fit into what was important or needed for us. There’s a very distinct line between Samantha and Kim. Samantha’s not gone. Samantha’s present, and I think was handled with such respect and elegance. She wasn’t villainized. She was a human being who had feelings about a relationship, so I think we found a way to address it which was necessary and important for people that loved her.”

TOPICS: And Just Like That, HBO Max, Sex and the City, John Corbett, Julie Rottenberg, Kim Cattrall, Michael Patrick King, Sarah Jessica Parker, Sara Ramirez, Sarita Choudhury

More And Just Like That on Primetimer:- Michael Patrick King stands by the 'Toilet Scene' and Carrie's solo ending on And Just Like That finale

- Who plays Mark Kasabian on And Just Like That? All about the actor behind the role

- And Just Like That Season 3 finale explained as Carrie decides her future

- Established IP Is All the Rage, But a Friends Reboot Is Still Off the Table