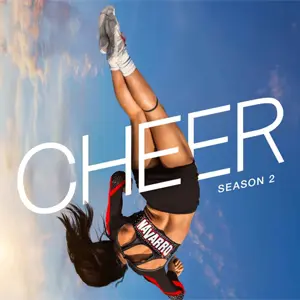

Cheer Season 2 reveals the double-edged sword of massive Netflix stardom

-

"A far less interesting version of Cheer Season 2 would have ignored how much of a phenomenon the show immediately became upon its January 2020 debut," says Caroline Framke. "Weeks before the pandemic brought most of the world to an unsettling halt, Netflix’s docuseries was an unavoidable smash hit, making overnight celebrities of its Texan cheerleader subjects whether they wanted the spotlight or not. They went on Ellen, Dancing with the Stars, and the Oscars red carpet. They became Instagram influencers and TikTok stars. They became characters both relatable and aspirational for millions of viewers across the world who suddenly felt incredibly invested in the results of a cheerleading competition. In its second season, Cheer could’ve just followed that story all over again, yielding decent results. It could’ve gone the Tiger King 2 route, only briefly acknowledging the series’ impact before reverting back to old storytelling habits. Instead, both by choice and by wild circumstance, the season that director Greg Whiteley and team created is a fascinating study of what it actually feels like to be part of a Netflix phenomenon that burns fast and too bright. Even before the pandemic hits and the team’s most beloved member, Jerry Harris, gets indicted on federal charges (more on that later), the second season of Cheer opens with the Navarro cheerleaders reeling from the shock of becoming famous in an instant. They scroll through their verified Instagram followers in disbelief, hug Kendall Jenner on TV, and take seemingly every single promotional campaign they’re offered. (A particularly painful early montage shows the squad listlessly cheerleading their way through an ad for a local bakery and a YouTube stunt on a nearby farm whose owner couldn’t care less about Netflix, let alone YouTube.) Coach Monica Aldama — a steely woman whose careful, deadpan affect is more curious than charismatic — quickly finds herself inundated by constant interviews and motivational speaking engagements. It all looks very exciting, but in talking head interviews, few of them seem excited about any of it. The team is still a solid unit in practices, but the unspoken tension of what the docuseries revealed, who got the most attention, and how much time their new extracurricular of being famous sucks up is all too palpable." Framke adds that Cheer Season 2 benefits from tackling Jerry Harris' indictment on charges of soliciting sexual images from minors from the get-go. "Making this reality plain right off the bat provides crucial framework for the season to come, which began filming well before the allegations broke, and continues throughout the squad’s subsequent collapse," says Framke. "A lesser version of this show might have omitted Jerry as much as possible, explained his fate in a quick sidebar, and moved on. But one of the reasons why Cheer became so popular in the first place was its palpable empathy for its subjects’ pain, and that goes double in this horrific instance."

ALSO:

- Cheer is uncomfortable to watch in Season 2: "Throughout this season, it feels like Cheer is trying to toe the line between telling hard, uncomfortable truths about the sport of competitive cheerleading while also being inspirational television," says Michael Blackmon. "In Season 1, you could actively applaud the Navarro team and its dedication to the sport, looking past the injuries the athletes sustained and the broken homes they escaped to make their dreams a reality. But Season 2, which was shot in 2020 and 2021, before and then during the pandemic, it feels icky to witness. Observing the young cheerleaders push past their breaking point and, even worse, seeing how the coaches poorly handle their emotions when it comes to the athletes’ needs illuminates the overwhelming stress of the sport."

- Season 2 is three shows braided together as one: "It’s a follow-up to the first season of the breakout Netflix docuseries in which we once again watch the Navarro Community College cheerleaders confront numerous obstacles while attempting to win another national title," says Jen Chaney. "It’s also a reboot of the first season that follows a new cheer squad, Navarro’s rival, Trinity Valley Community College, as their members deal with their own issues while trying to win a national title for the first time in several years. And thirdly, it is an examination of the effect season one’s popularity continues to have on the Navarro squad, as well as the unfortunate downfall of Cheer’s original breakout star, Jerry Harris. These three interrelated approaches result in nine episodes of sports-reality drama that are largely compelling but less focused than Cheer’s first season." Chaney adds: "Obviously this is a darker, heavier Cheer than season one. It would be irresponsible if it weren’t. But there are moments of uplift, too, and a lot of them come from the crew at Trinity Valley, coached by Vontae Johnson and his assistant, Khris Franklin, with as much heart and grit as Aldama gives to her squad. Given Navarro’s recent success and Netflix sheen, TVCC emerges as an underdog determined to unseat the community-college cheer equivalent of the New England Patriots."

- Cheer Season 2 is marked by a perhaps inevitable messiness that reflects the chaos of the past two years in and beyond Navarro: After Jerry Harris’ arrest, "it’s hard not to notice the show’s course corrections: the dimmed spotlight on the athletes, a softer portrayal of the still-reeling Aldama, intimations of the larger issues plaguing the billion-dollar cheer-industrial complex," says Inkoo Kang. "The result is a season missing much of the youthful heart that distinguished its predecessor, but it’s still a well-crafted sports drama and an enthralling showcase of this particular blend of acrobatics and flair." As for the handling of Harris' case, "creator Greg Whiteley’s tack is sensitive and responsible, interviewing the twin boys who came forward about their alleged harassment by Harris, the 'safe space' they lost in cheer after identifying themselves as victims of sexual abuse and the wider patterns of sexual misconduct — too many swept under the rug — that journalists compare to the Larry Nassar scandal in youth gymnastics," says Kang. "Season 2’s depiction of cheerleading is a more complicated one than the inspirational vision of Season 1. It’s no longer so immediately rootable, but its reckoning with the larger cheer world is thoughtful and necessary."

- Much of the big topics of Season 1 are put on the backburner in Season 2: "There’s so much happening and the narrative through-line becomes so fuzzy, you barely notice how many of the big talking points of the first season have been pushed to the background instead of benefiting from more exploration," says Daniel Fienberg. "For example, the first season was near-obsessed with injuries, probably because the filmmakers wanted to emphasize the harsh physical conditions in advanced cheerleading. But many critics of the show felt that Cheer ended up glorifying the bodily harm and the coaches and schools that exploit those bodies. So the second season has stripped away the pervasive sound of bodies crunching into the mats, of bones breaking and athletes sobbing in pain, keeping only regular vomiting in trashcans as a reminder. The show is still struggling to get into the sexual politics of the sport as well. The number of gay athletes came up in the first season primarily to illustrate that despite being a church-going Texan, Monica is still open and loving. The second season becomes more eyebrow-raising and less clarifying as folks hint at how appropriating an ostensibly or performatively gay attitude and swagger has been the secret of Navarro’s success, one that Trinity Valley struggles to copy, but then… it ceases to be a conversation point. Ultimately, the mess is only partially unintentional. While a six-episode, tightly produced season might have been ideal, these two years have been anything but ideal, and the new season’s structure probably needed to reflect that. The first season felt efficient and emotionally clear. In the second season, emotional clarity is impossible, and you can sense every choice the documakers are making — for better or worse."

- Sexual abuse is a topic Cheer handles with care and respect, devoting significant time to the survivors, not just the perpetrator: "The show makes parallels between abuse in cheerleading and abuse in gymnastics, both sports that put often very young children in unsupervised contact with adults; in cheerleading, adults can even compete on all-star teams with children," says Alison Stine. "But then the show moves on, although the athletes can't forget what their former teammate is alleged to have done, and the show can't, either. Even if Cheer doesn't talk about it again, his absence lingers like a long shadow." At one point, Aldama says, "I would like to have some closure and some clarity." But, says Stine, "real life doesn't have closure usually, not in the way we want it to, not in the way we hope. Cheer does a good job of existing in that middle space, a space where we don't know what's coming and we haven't recovered from what happened, not yet, maybe not ever."

- Cheer creator Greg Whiteley says he never considered not moving forward with the series in light of the allegations against Jerry Harris: Whiteley tells the Los Angeles Times he also doesn't feel that he had somehow misrepresented his subject in Season 1. “Human beings are complicated people," he says. "As a filmmaking team, we’re as good as anyone at creating a portrait and filming somebody authentically. But in the three months that we’re allowed to film someone, we’re not going to get to the bottom of someone. I think as long as we’re humble about that, and that when we do learn something new, we’re we have the integrity to also cover it, not ignore it, then I can sleep at night knowing I’m doing my job.” Whiteley adds: “This was an event that was so impactful on the lives of the team. Even if Jerry was no longer physically present while we were filming, his presence still was very large. You could feel a team that was completely devastated. It was as though a close friend they thought they knew had died. And that isn’t something that goes away in a week, or a month, or even a year.”

TOPICS: Cheer, Netflix, Greg Whiteley, Jerry Harris, Monica Aldama, Reality TV

More Cheer on Primetimer:- Cheer Star Jerry Harris Apologizes to Sex Abuse Victims After Being Sentenced to 12 Years in Prison

- Cheer Season 2 debuts at No. 2 on Nielsen's Streaming Top 10

- Cheer's Jerry Harris pleads guilty in federal child sex porn case

- Bring It On star Gabrielle Union pens an appreciation of Cheer breakout Jada Wooten