NBC's Law & Order revival feels like a walking corpse brought back from the dead

-

In a two-decade run, Dick Wolf's original Law & Order series eschewed melodrama, which is why it has endured as a fan favorite, says Nina Metz. With the Season 21 revival, however, "showrunner Rick Eid (a longtime Wolf veteran) has jettisoned much of the nuance and realism of the original in favor of something labored and clunky, as if the scripts were WRITTEN IN ALL CAPS and too often the actors follow suit," says Metz. "No one’s underplaying anything." Metz adds: "But more to the point, the episode is dull. Nobody functions as an intriguing foil to anyone else because there’s no chemistry. Scenes play out like clunky Twitter exchanges rather than two people talking with human inflection. The unwavering paradigm of a white male lead prosecutor paired with an extraordinarily gorgeous female helpmate is played out. And we see so little of the absurdist details that were always there amid the human tragedy. Or just the labor — the bit by bit efforts — involved in building a case. The show feels like a walking corpse brought back from the dead, but lacking any of the important animating qualities that made it standout in a well-worn genre."

ALSO:

- Law & Order is missing the things that made it essential: "There’s disappointment here, but not surprise," says Mike Hale. "The Law & Order that NBC abruptly canceled in 2010 was already long past its glory days, though it had perked up a bit in its last few seasons. The primetime empire of FBI, Chicago and Law & Order shows ruled by the producer Dick Wolf — he now has control of three full nights of network programming — is an exercise in the maintenance of audience-pleasing formulas. Based on the evidence, there was no reason to expect anything different. Still, you could hope that 'The Right Thing,' the show’s 457th episode, would at least buff up the old routines, make them shiny and snappy for a night. But the prevailing feeling, from the writing to the staging to the performances, is of people going through the motions and being careful not to knock anything over. It’s a ritual re-enactment."

- Law & Order hasn't changed, which is why it lasted so long: "Although an occasional narrative experiment might disrupt the format, what makes Law & Order special is precisely the fact that it has one, like a sonnet, a sestina, or an ottava rima," says Robert Lloyd. "You can dip in anywhere across the years, and whether it’s Jerry Orbach and Benjamin Bratt, Orbach and Jesse L. Martin, or Dennis Farina and Michael Imperioli beating the pavement, or Michael Moriarty and Richard Brooks, Waterston and Jill Hennessy, or Waterston and Angie Harmon trying the cases — or any other variation in personnel through the mix-and-match decades — and get the same effect, the same satisfaction. (Broadly speaking it is a show made up of questions and answers, on the case and in the courtroom.) In its very structural predictability, it wants to reflect the justice system it represents, which might go haywire from time to time — a fact the series actively acknowledges, and which is central to the season opener, the only new episode available for review — but is meant to give you the soothing sense, generally, that things are in good hands."

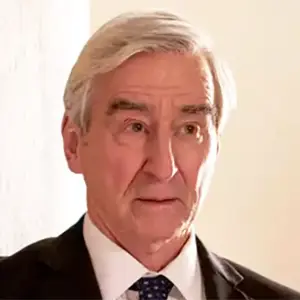

- Law & Order Season 21 delivers what longtime fans have always loved about the show: "For those of us who’ve watched countless classic Law & Order episodes over its first 20 seasons (1990-2010), the question is whether the 21st — a reboot premiering Thursday after more than a decade off the air — will satisfy fans?" says Thelma Adams. "With its mix of established cast members and new faces led by the indomitable 81-year-old Sam Waterston as D.A. Jack McCoy, and time-worn format, how can it fail? Dick Wolf’s baby has never jumped the shark and, while this new series doesn’t break new ground, it briskly covers the metropolitan landscape that we love, and sometimes love to hate."

- Jeffrey Donovan's troubled detective character Frank Cosgrove sets forward a challenge for Law & Order going forward: "To find ways, within the Law & Order framework, to depict a cop as foolhardy, as brash — as, well, wrong," says Daniel D'Addario. "Elsewhere in the episode, Cosgrove’s tactics to elicit a confession would seem, at least to this viewer, to stomp well past the bounds of ethics; the gray area in which the evidence he’s solicited exists creates a conundrum for A.D.A. Nolan Price (Hugh Dancy) and for his boss Jack McCoy (Sam Waterston, returning from the series’ original run)."

- A Bill Cosby-esque case isn't the right way to relaunch Law & Order: "Law & Order’s revival feels like a continuation in a slow franchise-wide turnaround," says Laura Bradley. "But these shows have always focused more heavily on plot than on social issues. This week’s premiere feels in keeping with the original formula, if a bit watered down—but its take only feels fresh if you’ve tuned out the rest of the franchise in recent years. There’s no question asked here (so far; it’s only been one episode, in fairness!) that has not already been asked in another corner of the Law & Order universe....Bill Cosby’s case seems like obvious fodder for a Law & Order episode, but in some ways this introduction starts the show and its cast off on the wrong foot."

- The Season 21 premiere was too much of a mess: "The Right Thing' is the series’ 457th episode and at least 456 of those were better plotted," says Stephen Robinson. "Classic Law & Order might’ve ripped stories from the headlines but the resolutions were never pedestrian. You might’ve safely assumed that King’s killer was anyone but one of his victims or that the murder would have nothing to do with his crimes. Unfortunately, it’s just that straightforward."

- In praise of Sam Waterston's Jack McCoy, who represented Law & Order's unresolved tension: "The most famous and beloved fictional lawyers tend to be defense attorneys, the Atticus Finches who are idealistic champions of the little guy," says Tim Grierson. "But for 16 seasons, Jack McCoy represented the prosecution, tearing into slimy lawyers and mendacious witnesses, telling off crooked judges and flouting the law if it was getting in the way of him nailing a crook. Sure, he got slapped on the wrist frequently. (He faced the possibility of disbarment a couple times, if I remember correctly.) But to my mind, Law & Order never really glorified this behavior...No character in Law & Order’s run was more flawed than Jack McCoy, which might explain why he was also among its most virtuous. In a sense, he represented the unresolved tension within the show: We want the good guys to put the bad guys behind bars, but what if that sometimes requires cutting corners or exploiting a legal loophole? The ferocity of McCoy’s passion was stirring — his closing statement in front of the jury was often an episode’s emotional highlight — but Law & Order was nuanced enough to quietly frown at his hotheaded demeanor."

- Presenting 20 essential episodes of Law & Order

- Ranking the 50 best episodes of Law & Order

- Camryn Manheim promises "uncomfortable" storylines, while Anthony Anderson says the transition from Black-ish back to Law & Order wasn't difficult: "We are really going deep and the writers are not afraid," says Manheim. "There's uncomfortable situations that we're just trying to get through. I mean, things are uncomfortable these days." Anderson jokes that he and Jeffrey Donovan are "making Law & Order a comedy and we don't ever tell any of the directors that come in. So they have to reel us in just because of the fun that we're having with one another."

- Sam Waterston credits the Law & Order revival with keeping "me from doing really dumb stuff": With a "decent" salary, the revival came as he began to worry about how we would pay for four college educations. “It was just exactly the right moment,” he tells The New York Times. “And it kept me out of trouble. Kept me from doing really dumb stuff.” What dumb stuff, exactly? "Well, who knows what the dumb stuff would have been,” he says. “But we all know that there’s a lot of dumb stuff.” Meanwhile, Dick Wolf says of Waterston: “He makes the role and the words unendingly interesting. That takes a level of skill and humanism that not many people possess.”

- While Dick Wolf says "there's nothing to fix," Sam Waterston hopes the revival gets viewers to throw their shoes at the TV: “There’s nothing to fix; we just want to continue telling great stories,” Wolf tells Variety of Season 21, adding that the same goes for the show’s take on the cultural landscape and the nation’s many divisive issues. But Waterston says "we’re not shying away from any of those (timely) conflicts. In fact, it’s always been the goal of the show to get people throwing their shoes at the television, and certainly there are issues that are going to infuriate people and frustrate people about how they turned out. That’s the pleasure of watching Law & Order; there is a resolution but there’s a lot of dissatisfaction with the way it goes. It feels, to me, like Law & Order might have something to contribute to the general conversation because we’re all mad about something. We’re all mad as hell about something right now and mad at each other. For us to get these big issues aired, and to have not a conclusion but a resolution of some kind that you can chew on, might be a useful service.”

TOPICS: Law & Order, NBC, Anthony Anderson, Camryn Manheim, Dick Wolf, Jeffrey Donovan, Rick Eid, Sam Waterston