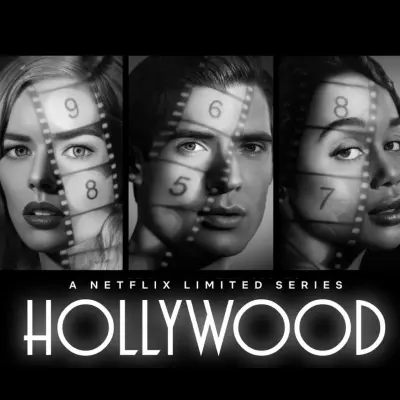

Ryan Murphy's Hollywood is laughably self-satisfied and willfully naïve about complex real-world problems

-

"Is it possible for a fantasy to be too absurd?" asks Aisha Harris of Murphy's Netflix alt-history series. She adds: "What if a handful of straight (and ostensibly straight) white people were actually willing to risk their careers and reputations in order to create opportunities for the underrepresented? Both counterfactuals are played out in Hollywood, but they rest oddly alongside one another — one is playfully subversive; the other a retread of simplistic progressive logic about how to combat systemic oppression. The show’s appeals to the benevolent hearts and minds of 'good' people are maddeningly naïve. I devoured each episode anyway. A pattern develops throughout the series: Someone white or white-passing makes an impassioned plea for a more powerful white person to take a chance on hiring a person of color for a role. The argument is framed purely in do-gooder terms — an opportunity to 'change the world,' to look back on this moment years from now knowing they 'did the right thing.'" The problem, she says, is that Hollywood doesn't reflect reality. "That’s because history has proved that even for those who have been sympathetic to the causes of the marginalized, there’s only so much power they are willing to concede. It’s how we end up with, say, the North capitulating to the bruised egos of the side that lost the Civil War, or politicians catering to the religious right in the race to ratify the Equal Rights Amendment," says Harris. This has been as true of the entertainment industry as it has been of government — which is why it remains a big deal when a Black Panther or a Crazy Rich Asians or a Wonder Woman gets made, much less finds success. Those films were borne of hard-won fights for equality. And yet I keep coming back to the happy endings of the Hollywood characters. There is something to be said for the show’s fluffy confection of ahistoricism when it’s not indulging in myths of racial reconciliation and movies-as-changemakers."

ALSO:

- Why does Ryan Murphy's Pose revisionism seem so necessary, while Hollywood's feels so insulting?: "After a saccharine debut season that merited a comparison to Full House, Pose became, in its sophomore year, one of TV's best and most urgent dramas by balancing its encroaching darkness with a 'fairy-tale' wistfulness," says Inkoo Kang. "(The great majority of its characters not only keep outrunning death by AIDS or murderous transphobia, but also get to pursue their dreams.) The drama pays tribute to the trans women and gay men of color of the 1980s and 1990s by reminding us that they were individuals before they were members of an endangered demographic. Hollywood, on the other hand, doesn't let its characters be more than specimens of oppression. We learn precious little about Camille, and as a director, Raymond seems far less motivated by the art of storytelling than by the prospect of getting his thwarted role model, Anna May Wong, and later his girlfriend and his screenwriter, trophies. Wong is a victim of Hollywood typecasting, but we never really learn what kinds of characters she would like to play. (Her role in Meg is conspicuously undefined — what matters is that she wins an Oscar for it.) Archie is somewhat humanized by his romance with Rock Hudson (Jake Picking), but as he's written on the page, he's all ambition, no core. Hollywood thinks it's championing its characters of color, but it can only see them as victims, then miraculous victors."

- Murphy's fun thought exercise curdles into earnest nonsense: "As a producer, Murphy usually succeeds in excavating the complex, uncomfortable truths in dramas about history: In The People v. O. J. Simpson, he exercised restraint while telling the most tawdry of true-crime tales; in Pose, he found subtlety in the most exuberant ballroom worlds; and in Feud: Bette and Joan, he criticized the machinations of old Hollywood’s most glamorous icons," says Shirley Li. "But in Hollywood, he resorts to wishful thinking, never demonizing the industry and its Hays Code era, leaving the series toothless instead. The show acknowledges the sexism, racism, and homophobia of the postwar movie business, but it treats such systemic issues as simply failures of imagination—as if all Hollywood needed was more Roosevelts bravely striding onto movie sets."

- Michelle Krusiec fights back tears discussing her Anna May Wong portrayal: “Even when she was wearing her Oriental dresses, there was something modern about her,” Krusiec says. “It was something in her ability to wear clothes that was both of-the-period and yet modern, and that’s what I think they tried to capture.”

TOPICS: Hollywood, Netflix, Michelle Krusiec, Ryan Murphy

More Hollywood on Primetimer:- Did Cora Susan Collins have a husband and a kid? Family details explored as tributes pour in for actress' death at 98

- Ryan Murphy's work is suffering on Netflix: He now seems to favor winners over underdogs

- Ryan Murphy's Netflix Report Card

- Ryan Murphy is now 0 for 3 with his Netflix shows, at least in terms of critical acclaim