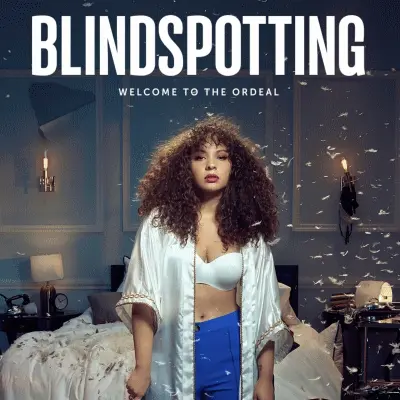

Starz's Blindspotting is less a continuation of the acclaimed 2018 movie than a smart expansion of its world

-

"Blindspotting isn’t the most obvious candidate for a film-to-TV spinoff," says Alan Sepinwall. "The 2018 movie, co-written by Rafael Casal and Daveed Diggs, who star as best friends in Oakland, made less than $5 million at the box office. It was well-reviewed but not a major awards player. And its stories — Diggs’ ex-con Collin finishes out his probation, while Casal’s Miles rails against gentrification — didn’t leave lots of open questions demanding a sequel, on the big or small screen. But Blindspotting the series, debuting this weekend on Starz, is less a continuation of the film than a smart expansion of its world. Some of the original characters are back, but the show is built in a way that doesn’t make the movie required viewing for newcomers. Instead, it feels of a piece with what Casal and Diggs (who return as writer-producers) did earlier while functioning as its own satisfying, serio-comic slice of Oakland life. In one episode, a character even summarizes the events of the film for a new friend, then says, 'Yeah, it was a whole movie. Sh*t is just different now, I guess.'" Sepinwall adds: "The actors — (Jasmine) Cephas Jones and (Helen) Hunt in particular — seem comfortable navigating the series’ slippery tone, where scenes can shift from low-key to magical realism without warning, in the same way that Trish deftly code-switches while seeking a small-business loan when she sees she’s been paired with a black banker. And if Ashley feels initial discomfort about her move, particularly where Trish and her various side hustles are concerned, the ensemble settles quickly into a welcoming hangout vibe. You’re just as likely to hear Earl expounding on why the 1993 Robert Townsend superhero movie Meteor Man is responsible for both Black Panther and the Obama presidency as you are to see him panic about getting busted when a job interview threatens to keep him out past curfew. Like the movie, the series is ultimately a love letter to the multicultural stew of Oakland, even as it acknowledges the way the city, like most of urban America, is rapidly changing."

ALSO:

- Blindspotting is as worthy a reimagining as it gets, particularly in the series’ visual flights of fancy: "The series is less a remix than an inspired riff on its source material, with a decidedly female-centric perspective on gentrification, the justice system and the hardships of raising a family amid crisis and trauma," says Inkoo Kang. "Spoken word and spare but evocative dance sequences amplify the characters’ emotions, rendering the show yet another of Starz’s hidden gems about artistically vibrant communities of color under siege (Also see: the strip-club noir P-Valley and the deliciously thorny gentrification drama Vida)." Kang adds: "One of the driving forces of Blindspotting the film was the sense of dislocation you can feel in a place you’ve lived all your life. That feeling carries through — with new valences — in the adaptation. Ashley, in fact, refuses to let herself get too comfortable in Rainey’s home, opting to sleep on the couch instead of with her son in Miles’s room. After a violence-filled childhood, she’s figured out how to put others at ease, and doing so professionally as the concierge at a fancy hotel bought her a nicer life, at least for a while. But as Trish is happy to remind her — always in the form of a jab — Ashley doesn’t quite know how to fit in the neighborhood she grew up in anymore. Her young son might belong even less. Unlike many other film-to-TV adaptations, Blindspotting leans heavily on its episodic structure, lending each chapter a distinct shape and vibe. Ping-ponging between the beach and prison, bookstores and taco trucks and local car-stunt exhibitions (known as 'sideshows'), the series is the rare well-rounded portrait of contemporary Oakland. Even more rewarding are the layers of history between the characters that the season gradually uncovers, especially between Ashley and Rainey, whose lives have intersected for more than a decade. The show’s writers — Diggs among them — delight in rapid-fire verbal play while conveying the struggles of parolees like Earl and parsing out the socioeconomic differences among the Black characters without ever falling into didacticism."

- Blindspotting is the best film-to-TV adaptation in years: "Where this brilliant series most notably succeeds is in repositioning the same type of story within a new perspective, all while tackling how someone’s actions affect the lives of those around them," says Kayla Sutton. "The show borrows heavily from the film, incorporating verse, fourth wall breaks, and isolating cutscenes, and stretches those moments to fit within Ashley’s perspective. Seth Mann (Homeland, #FreeRayshawn) directs the first few episodes, and his style seems heavily influenced by Spike Lee. But it’s fantastic to see how that influence creates a truly immersive and modern viewing experience."

- It’s exciting to see a film adapted to television in such a productive way, successfully expanding the world and its characters: "Throughout the six episodes available to review, Casal and Diggs’ writing is a compelling combination of commentary and entertainment, inviting us to think about the larger prison industrial complex and how it affects entire families, while still having moments of levity," says Kristen Reid. "Like the film, the Blindspotting series injects spoken word poetry and rhythm into various scenes as well. Moments of high emotional tension are addressed with fourth wall breaks and verses spoken directly to the audience. Breaking the continuity of the story to blend the narrative with unique sequences defines the show’s aesthetic. In one episode, Ashley walks by a photo of Miles and Collin in their younger days and imagines a version of them dancing through the home. Dramatic lighting choices bring us in and out of these musical moments effectively. Even in the scenes where there aren’t direct breaks in the story, background characters are seen dancing and moving in choreographed synchronicity; music and rhythm remain a core aspect of the Blindspotting world. By expanding the film into a television show, it allows these unique aspects to further develop and create an even stronger story, one with a pointed focus on the struggles of those left behind by a sudden arrest."

- Starz's Blindspotting may evolve into the definitive version of the story: "I thought the 2018 feature Blindspotting was a mess, but it was the sort of mess more movies should aspire to be," says Daniel Fienberg. "Daveed Diggs and Rafael Casal’s screenplay took big thematic swings and Carlos López Estrada’s direction was full of bombastic flourishes — part dark comedy, part musical, part polemic, part Bay Area travelogue. Even the plot beats that didn’t come together were surrounded by big ideas and beautiful things to listen to and see. Starz’s new TV adaptation of Blindspotting lacks what was probably the primary source of the movie’s appeal, namely the rapport between longtime friends Diggs and Casal, and it doesn’t aspire to exactly the same level of finger-on-the-pulse agitprop. But it may end up evolving into the definitive version of this story. Through the six episodes sent to critics, this Blindspotting quickly settles into its own confident voice, and the characters, especially the new faces, are proving to be appealing vehicles for some of the same themes and more...It’s provocative, funny and, like the film, seems initially allergic to subtlety. Jones is a thoroughly sympathetic center to the story and she slays the spoken word interludes, which never feel quite as organic coming from her character as they did from Diggs and Casal. Most impressive is how well the series works when it’s quieter and less performatively dogmatic — traits associated with Collin and Miles — and lets the voices of the new cast of characters take over."

- Blindspotting proves to be mighty savvy with its expansion, starting with how it echoes the film’s opening credits: "It’s no longer an image of Oakland’s famous Fox Theater playing a movie called Blindspotting; the whole venue has been renamed to Blindspotting, and now the chapters are on the marquee as if they were their own production," says Nick Allen. "It’s a vital nod to how this isn’t just about Oakland, but this entire universe that’s now filled with new characters. Blindspotting the series is not as tense a universe as the film — sometimes it can be a little too slack — and it doesn’t juggle loaded issues as openly. But this show gets you into its new groove, and it leads with the same artistic abandon that made Blindspotting beautiful. In its expansion of the Blindspotting universe, one that started with Daveed Diggs and Rafael Casal’s buddies Collin and Miles, the series works from what could be considered a flaw in the movie: the lack of proper screen-time for Ashley, Miles’ girlfriend and a secret weapon from the movie."

- Blindspotting is wickedly entertaining as dreamlike hip-hop fantasy and gritty, real-world drama -- with a surprising Helen Hunt performance: "Helen Hunt PLAYS Miles’ free-spirited, progressive, bohemian mother Rainey, and while Hunt might not be the first actress you’d think of to take on such a role, she knocks it out of the park as a woman of a certain age who has a live-and-let-live attitude about sex, drugs, relationships, you name it — but is fiercely loyal to her grown children and will do anything to protect her young grandson," says Richard Roeper. "It’s the finest work we’ve seen from Hunt in years."

- Blindspotting's thematic elements read as undercooked and its visual ambition isn’t smoothly stitched to the primary narrative: "Instead of vocalizing how gentrification is slowly eroding the Bay Area, the writers on Blindspotting carve grating character dynamics," says Robert Daniels. "Ashley and Trish are the biggest culprits, as they share an antagonistic relationship stemming from Ashley advising Miles not to invest in Trish’s idea for her own stripclub run by women replete with a cooperative union. But in actuality, these two invite trouble like ice on a dark highway—Ashley routinely shames Trish for her revealing attire while Trish questions Ashley’s credentials as a mother and member of their family. Speaking of moms, it’s not altogether clear how Rainey fits in these subplots. Hunt pulls together a character who just isn’t a believable mother for Miles or Trish. In other words, how did a hippie white mom raise a black daughter and white son to be hood? This show desperately wants to elicit serious conversations. These explorations, however, always feel half-finished. Part of the underdevelopment stems from the odd framing: how does one explore the effects of prison on a Black mom and son when the incarcerated father is white? Centering Ashley as the chief viewpoint greatly helps."

- It's a Hamilton summer with Blindspotting arriving on the same weekend as In the Heights: Jasmine Cephas Jones stars in Blindspotting and her Hamilton co-star/real-life fiancé Anthony Ramos stars in In the Heights while also making a cameo on the Starz series, which Hamilton alum Daveed Diggs co-created.

- Co-creator Rafael Casal recalls being "really opposed" to making the show after spending a decade making the film: "I remember Lionsgate was like 'I think we should make a TV show.' and we were like, 'I don't think we should. I think it's already been done,'" he says. "It's because we were thinking, Miles and Collin longer story. What are we going to talk about with the two of them? (The movie) was the most interesting three days of their lives, but we went into a meeting because Lionsgate are friends of ours and main collaborators. We took the meeting and were like, 'Look, we only want to do it if we could have it be all about Ashley. That's the character we actually wanted more from in the movie,' and they were really on board with that."

- Casal was stunned how quickly and completely Jasmine Cephas Jones built out her character while filming the Blinsdpotting movie: “She created an Ashley that felt truly full in her complexity in such a short amount of time,” says Casal. “When somebody uncovers that much about a character in so few scenes, that screams that they need more scenes.”

- How Helen Hunt ended up on Blindspotting: "I saw the movie and I loved it, and I posted about it (on social media). Rafael commented on my post, and I commented on his comment and we direct-messaged and a week later we were having a drink somewhere," says Hunt. "I love his work, and apparently he didn’t hate mine, so we talked about making some work together, and about all sorts of different things. We struck up a friendship, and with Daveed as well, and the three of us were working on writing something for a while. We spent a good part of the pandemic on my lawn watching old movies on a projector and a screen that I bought. One of the nights they were over they got the call that Starz was going to make Blindspotting into a TV series and they made these little jokes, like 'There’s a little part, but you’re never gonna do it,' and I just let it go by because I know that mixing work with friendship sometimes can be tricky unless people really communicate well. There’s just a thousand ways it can go wrong, so I just didn’t say anything until Rafa (Casal) went, 'We have to talk about it now because it’s real and we really want you. Starz and Lionsgate want to, so what do you think?'"

- How Jasmine Cephas Jones reacted to Rafael Casal and Daveed Diggs writing a Blindspotting sequel series revolving around her character: Rafael and (Daveed) are very good friends of mine and they very specifically wanted to write something for me — something I could shine in — and when you have writers and friends who are really, really talented and want to create a world for you, but also know your talents and what you’re capable of, I knew they were going to write something for me that no one else was going to be able to write," she says. (This includes) all of the heightened things I do and the emotional roller coaster that Ashley goes through. To look at Ashley in a brand-new light and what is her backstory; who was she before Sean, and what was that like, having all of those complications, it was almost like creating a new character because we’re now talking about circumstances and situations Ashley’s in that she wasn’t in the movie and you get to see all of these different sides to her that you didn’t get to see (then)." Jones says of her character: "I don’t think she’s very different from what I’ve always thought of her. I think, just emotionally, seeing how strong she is as a mother and a person, that opened my eyes more to who she is. She does everything she can do for her son, and sometimes it might not always be the best decision but you know deep down she’s doing everything she can under these circumstances. She’s a superhero in a way, like a lot of mothers are, or a lot of women whose other halves are in jail. You don’t usually get to see those stories — we usually see the story of the person that is incarcerated and their journey — but the women hold the family together."

- Jones calls Blindspotting a "great contrast to the film": "It's like, we got the men's side, and now here is the women's side - and it works," says the Emmy and Grammy winner of the predominately female cast of characters. "It was something that was very important to them, and immediately I was completely down, and I thanked them for giving these women's stories a chance."

TOPICS: Blindspotting, Starz, Daveed Diggs, Helen Hunt, Jasmine Cephas Jones, Rafael Casal

More Blindspotting on Primetimer:- The Most Anticipated TV Shows of April 2023

- LeVar Burton and Katlynn Simone Smith among four joining Blindspotting for Season 2 -- rappers E-40, P-Lo and Too $hort to guest-star

- Independent Spirit Awards' TV nominees include Reservation Dogs, Blindspotting, We Are Lady Parts, It's a Sin and The Underground Railroad

- Starz renews Blindspotting for Season 2