Why Is Hate-Watching on the Rise?

-

Velma, Emily in Paris, Love Island U.K. (Photos: HBO Max/Netflix/ITV/Hulu)

Velma, Emily in Paris, Love Island U.K. (Photos: HBO Max/Netflix/ITV/Hulu)Welcome to Platform Shift, a column about the way the internet changes how and what we watch on TV.

Here’s a question that’ll colonize your brain if you’re not careful: How do you define hate-watching? It seems easy enough — hate-watching is intentionally watching a TV show that you hate — but it gets stickier the more you think about it. For example, hate-watching could contain:

• TV shows with intentionally hateable characters, like Game Of Thrones

• TV shows that with unintentionally hateable characters, like … And Just Like That

• Trashy TV shows that viewers “hate themselves” for watching, like Love Island

• Campy TV shows that are “so bad they’re good,” like Firefly Lane

• Divisive TV shows that people seem to genuinely loathe, like Velma.Are all of these hate-watches? Some of them? Hard to say. I got interested in the question based on a hunch that hate-watching, more broadly, was increasing, or that at least conversations about it were. This began, of course, with Velma. The renewal of Netflix’s near-universally derided show from earlier this year suggested that amidst increasing competition from other streaming platforms Netflix was looking for engagement at any cost. A recent New York Times profile of Netflix’s new marketing chief detailed an increasing emphasis on shows that “pop,” citing in particular the megahit Wednesday.

But might there also be, I wondered, a sort of dark pop possible? A “hate pop” that moves the needle in a different but quantifiably profitable manner understandable only by the eldritch intelligences floating within a data-analysis tank at Netflix HQ?

I came across a study in Variety from 2016 conducted alongside the text analysis platform Canvs AI, which suggested something intentional about all of this: that hate-watched dramas lead to increased viewership at twice the rate that love-watching does. To figure this out, the analysts cross-referenced Twitter comments with Nielsen ratings, algorithmically matching each tweet with one of 56 “emotions.” They found that each percentage point increase in “hate”-related commentary lead to a .7% increase in TV viewership for the next episode, which was twice the correlating uptick in viewership for shows with “love”-related commentary. I emailed the company to see how the data may have changed in the seven years since then, and they offered to just run a completely new report.

The results confirmed parts of my theory and borked others and sort of melted my brain. The company’s platform has changed a little in the intervening years, but the basic gist is that they help companies assess sentiment from large sets of open-ended text. While they still focus on TV and work with several major networks and streamers, they also help non-TV brands do things like quantify sentiment from customer surveys. For my purposes, they pulled directly from Twitter back to the beginning of 2021 and analyzed around three billion tweets for “hate” and “dislike” comments. (These don’t necessarily need to include the exact words to qualify as “hate” or “dislike”; vomit emojis or phrases like “this is trash” would suffice.)

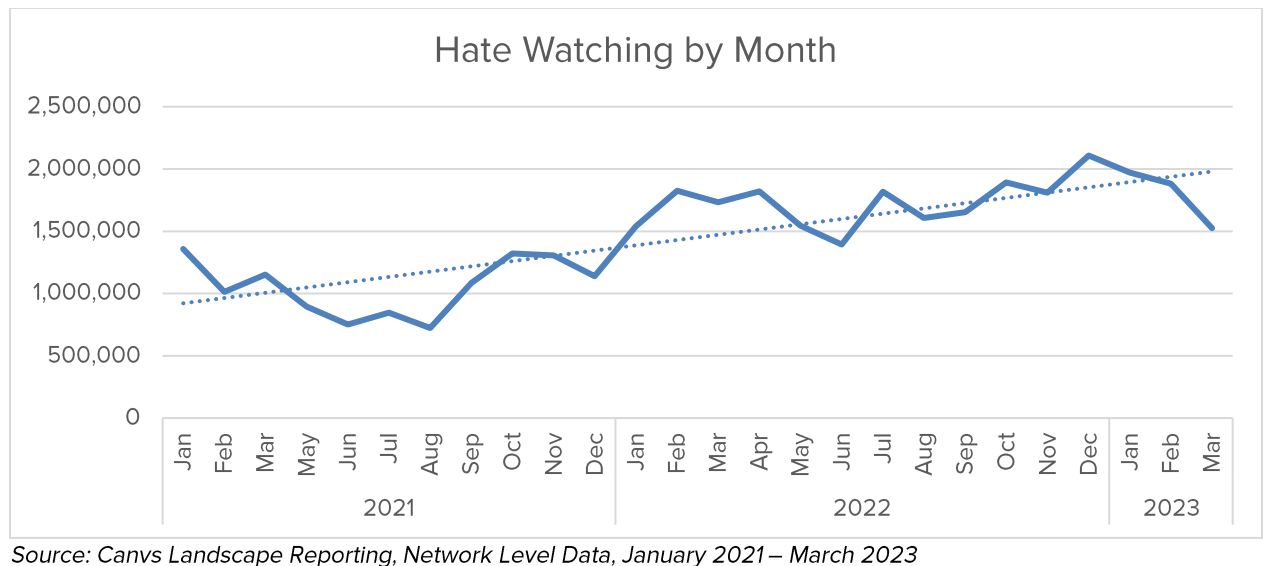

The study found that hate-watching increased 79% between 2021 and 2022, with steady continued growth at that rate through the first quarter of 2023. Sorting between network, cable, and OTT (or streaming), streaming shows saw the highest increase in hate- watching, increasing 191% year over year. And if you slice that data even further, Netflix leads the charge, accounting for over 50% of all hate-watching comments on OTT networks. In 2022, the quantity of Netflix’s hate-watching comments increased 156% year over year.

So, is hate-watching increasing? At least according to this data pull, the answer is yes. But it’d be wrong to say that Netflix is leaning into it. First off, just in terms of scale, it makes sense for them to have the most commentary online. Second, Netflix’s rate of hate-watching doesn’t come close to matching Hulu’s, which increased a gobsmacking 1,468% in 2022, with positive commentary only increasing 357%.

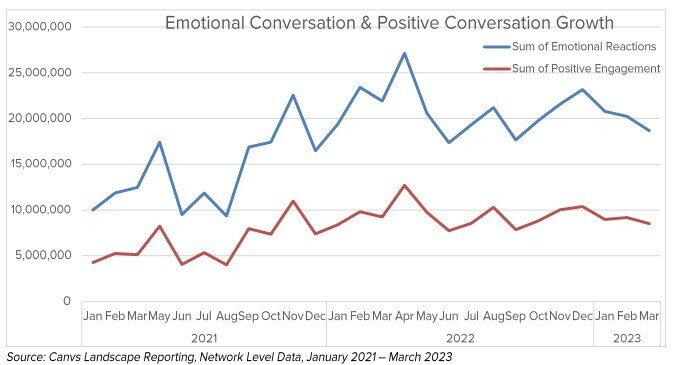

Third, when Canvs ran the data for all “love”-related comments, they found that positive comments had gone up globally, too, increasing 62% year over year across all shows. While hate-watching (at 79% growth) clearly outpaces it, the truth is that emotionally charged conversation around all television has increased over the years in question.

Why, exactly? That’s where things get interesting.

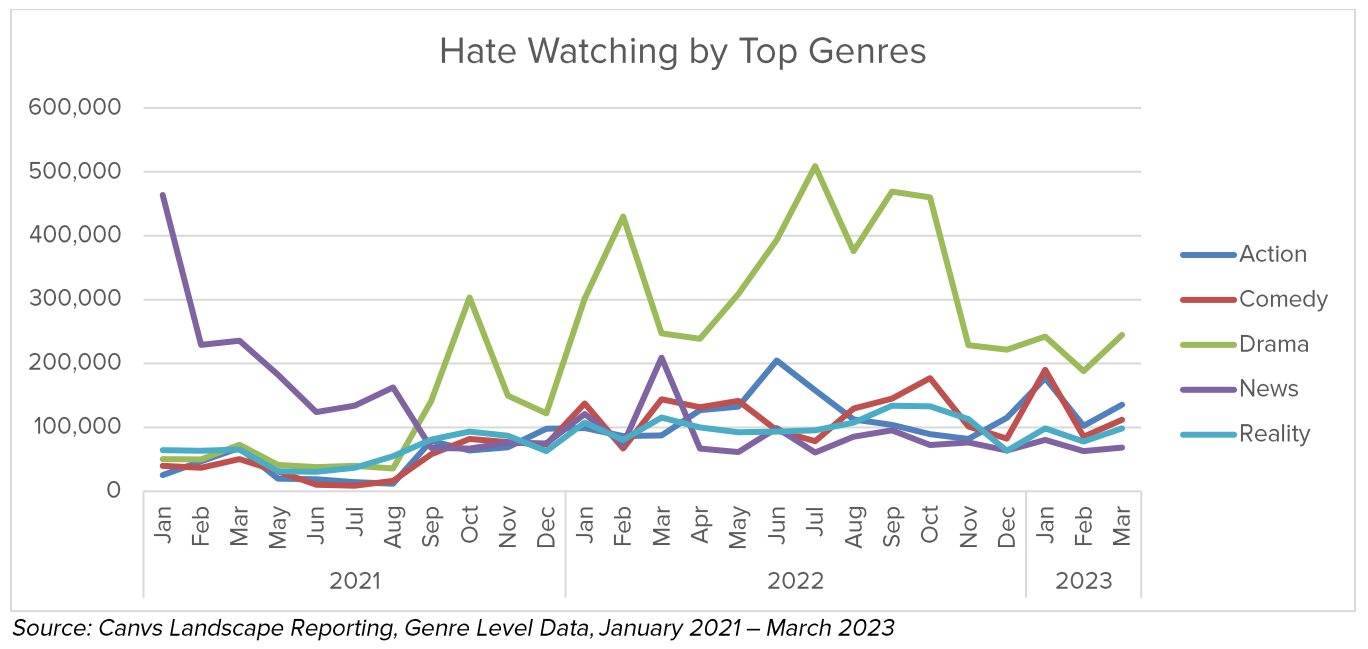

While Canvs’ data pull couldn’t easily be attributed to particular shows, it could be sorted by genre. See that purple line on the far left that takes a nose dive in January 2021 and then stays there? That’s news. What occurred on the news in January 2021? What recurring, hate-driving feature may have left the news cycle beginning in spring 2021?

I’ll stop being coy about it: I’m talking about Donald Trump. It’s a shame, for this specific line of inquiry, that the data can’t be pulled back to explore the intensity of hate-related commentary throughout, say, the late ’10s, to see how emotions toward the news rose and fell throughout the Trump presidency. But a clear story is told here, in which the recent animosity of American politics has, per Joe Biden’s campaign promises, dissipated somewhat, finding a safer home in conversations about TV dramas. That all conversation around television (positive and negative) has risen over these years suggests that people have emotional energy left to expend on TV rather than the sheer exhaustion that dominated the Trump era.

That all hits a little close to home — probably for everyone, but as someone working in the media during the onset of the Trump years, I saw firsthand the way his name could lead to an immediate skyrocket in (shiver) engagement. When you’re fighting for your life in a war for people’s attention, and a shortcut like that presents itself, it’s easy to take. Many news organizations have pledged to do better in the coming election cycle. I’m not totally sure it’ll work. But my hope is that we’ve all found something better to watch.

Maybe Firefly Lane— and Love Island, Resident Evil, even Star Trek: Picard, and so on — can take some of that energy. What is it about dramas in particular that inspires such animosity? Comedy’s unlikable characters come softened by their context, maybe; drama feels real, the stakes enhanced by the time we’ve spent with the characters. It’s easier to beef with drama showrunners, too, whose plotting has to be airtight.

I’ll be honest, though, that I’m not a big “hate-watcher” — if I don’t like something, I don’t want to waste time on it. But what I’m increasingly thinking is that hate-watching isn’t really a thing at all. It’s a term, sure, but an overused and nebulous one, conflating too many different aesthetic experiences under one umbrella. We bring the full complexity of our emotions to TV, and extreme distaste is just one of many possible flavors, built into the ongoing way we experience the medium. It’s possible that more shows will seem almost intentionally designed to inspire these strong negative emotions, as Velma (for example) did, but the solution to that gets at the oxymoronic nature of the word “hate-watching” itself. If you truly hated a show, you probably wouldn’t be watching it at all.

Clayton Purdom is a writer and editor based in Shaker Heights, Ohio. You can see other things he writes on Twitter.

TOPICS: Hate-Watching, Hulu, Netflix, And Just Like That, Emily in Paris, Firefly Lane, Game of Thrones, Love Island UK, Velma, Hate-Watch