A Taxonomy of Product Placement on TV

-

(Photos: NBC, Sony Pictures Television, FOX, HBO)

(Photos: NBC, Sony Pictures Television, FOX, HBO)FOX debuts its new game show Cherries Wild later this week. At first glance, it looks like Slot Machines: The Game, but in reality it's one giant, shameless plug for Pepsi. Which is cringeworthy for sure, but it also places the Jason Biggs-hosted show squarely within a TV tradition as enduring as television itself: shameless product placement. The manner in which TV shows have chosen to integrate products into their shows — in exchange for ad dollars that keep them afloat — has evolved over time. It's also something that's been as vexing for artists as it's been lucrative for networks. On the occasion of Pepsi's latest intrusion into our entertainment lives, here's a look at the many different ways product placement has been presented on TV:

The Classic Branded Show

When we say that product placement has lived in the bones of the television industry since its inception, that's not an overstatement. The earliest days of TV were an advertising medium first and an entertainment medium second. Some great television came out of those years, and some legendary performers. But those TV shows and performances often came wrapped up in packages like Kraft Television Theater, Texaco Star Theater, and even an anthology series called The United States Steel Hour. (Hey, U.S. Steel wasn't gonna sell itself.) And even when the TV shows weren't named after the products they were advertising, their commercial endorsements were not hidden, most often with the performers from the shows taking a break to shill for the products themselves.

Regular Old Product Placement

This is the 90% of product placement seen on TV today. As we got away from the '50s and television moved further into being an artist's medium, it started to feel gauche to shill so blatantly for processed cheese or alloyed metal. But the shows still needed to make money, especially since they were airing on free TV. So in addition to commercials, series began integrating products in more subtle ways. The bulk of product placement doesn't stand out to anyone's modern sensibility because a) we've been doing it so long, and b) we live in a world of brands anyway.

Product Placement As Text

The fact that brands are so much a part of our everyday lives means that they can be written into plots without even seeming like advertisements. Some of them aren't even advertisements, which makes it even harder to spot when you're being sold to and when you're just being told a story that lives in a universe where Apple, McDonalds and Kleenex are just a part of our lives. The concept of "a trip to IKEA" is such a recognizable part of domestic life that both 30 Rock and The Wire incorporated the home furnishings store into storylines. 30 Rock — a show that dealt with product placement in a lot of ways — had an entire episode where the end goal was to obtain a delicious McFlurry, which was both relatable and made the audience rabid for McFlurries.

Seinfeld was the king of using brands as part of the text of their show, reasoning that if their show was going to be about the trivial details of urban life, it made sense to reference the trivial brands that make up that life — from Drake's coffee cakes, to Juju Fruit, to Prell shampoo. The gold standard of this was the episode called "The Junior Mint," wherein a surgical observatory went wrong and Jerry and Kramer accidentally launched one of the name brand chocolate mints into the open cavity of a patient. Even amid that comedic horror, Kramer was able to get in a little endorsement for the candy.

Sarcastic Product Placement

The worlds of art and commerce butting heads is nothing new, but this happens a lot on ad-supported TV. Writers and performers don't always love the idea of their work being used as a vessel to sell Crisco or Microsoft or whatever. So when product placement becomes a necessity, shows will often write that into the show in order to either play the sponsorship off as a joke, or just make it seem more organic to the story. Community took its KFC sponsorship and built a whole tense space-pod adventure around it.

30 Rock again hit this vein with their Subway sponsorship, which took the Wayne's World tack of being super duper extra obvious about the product they're selling, making it seem like more of a joke than an ad.

Product Placement as Criticism

The more thoughtful avenue than the sarcastic product placement is to use product placement as a way to criticize product placement. A show like Mad Men was positioned to do exactly that, set as it was within the advertising industry and peopled with a bunch of amoral go-getters. Most of the products that Mad Men dealt with were relics from the past like Lucky Strike cigarettes or even Kodak, but the series finale struck one final blow at a giant: Coca-Cola and their famous "I'd like to buy the world a Coke" jingle, which, set against Don Draper's unsettlingly placid smile, felt more insidious than ever.

Reality TV

The golden age of reality TV was also a golden age for product placement that made sense. After all, these shows were giving away rewards and prizes. It only made sense that the advertisers be explicitly name-checked as the rewarders. Some of the more memorable instances of product placement on reality include Survivor rewards from Outback Steakhouse and Applebees (not to mention car giveaways like that hideous Pontiac Aztec that Colby Donaldson won); the Travelocity Roaming Gnome who's become an annual presence on The Amazing Race; the American Idol Ford commercials which happened every single week; Top Chef's prize package from The Glad family of products; the various accessory and makeup sponsors on Project Runway, from L'Oreal to Banana Republic; and of course America's Next Top Model and their iconic Covergirl ads. The nadir of this all, unsurprisingly, was The Apprentice, where every week the concept of being a businessperson was humiliatingly reduced to doing free marketing for whatever brand Mark Burnett's show had rounded up that week, though not before Donald Trump espoused that brand's corporate bona fides in stilted monotone.

In-Network Chumminess

This is a bit of a gray area since it often involves crossovers, which are a different animal, if under the game general genus. The Simpsons famously had a crossover episode with fellow FOX animated comedy The Critic, wherein Bart Simpson decried the lameness of cartoon crossovers like when The Flintstones met The Jetsons. More insidiously (though often just as obvious) is when shows will have characters talk openly about the programming on that same network. For years, ABC's soaps like General Hospital would feature characters making plans to watch that weekend's Oscars... on ABC, natch. More recently, and somewhat hilariously, NBC's The Weakest Link game show has prominently featured questions about NBC programming .

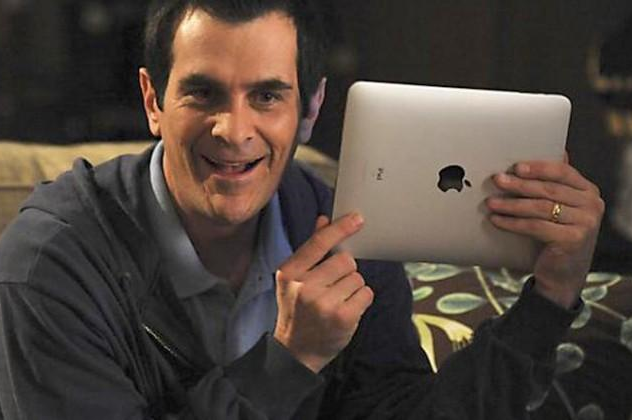

The Brand Behemoths

If brands have become central to our lives, that goes double for Apple products. Almost any show set in modern times needs to use computers, and those computers are either explicitly branded as Apple, have their Apple branding covered up because the show doesn't have Apple sponsorship, or else they're using another brand, which oftentimes feels inauthentic. This is also true of something like Google, which is so ubiquitous that referencing any other search engine by name sounds insane. See Hawaii Five-0 and their characters' frequent use of the phrase "Bing it" to search something. Happy that Bing is using their ad dollars, but… "Bing it"?

Sometimes shows without Google sponsorship will invent fake names for search engines to get around the name brand. It almost always sounds silly, although credit to a show like The Good Wife for leaning into that silliness by inventing a tech company called Chumhum and making them the law firm's most important client.

The Kings of the Road

Even more omnipresent than computers are cars, which offer networks and shows a plethora of product placement opportunities… as well as plenty of chances for shows to make it embarrassing. This practice goes all the way back to the black-and-white era of television, when Leave It to Beaver's Cleaver family would get a new Plymouth automobile every season. More modern shows like Alias, Heroes, Fringe, and 24 have shamelessly included glamour shots of the cars — including close-ups on the logos. Chicago Hope even went so far as to name a character "Lisa Catera," because their sponsor Cadillac had a car called the Catera… which one could lease… Lease-a Catera. Yeah.

Show-Saving Brands

Sometimes for a show that's struggling in the ratings and on the precipice of cancellation, product placement can actually be a saving grace. That's famously the story of the NBC dramedy Chuck, which was languishing but ultimately brought back for a third season in part because a product integration deal with the Subway sandwich chain gave NBC a financial incentive to do so. Brands: is there anything they can't do?

Joe Reid is the senior writer at Primetimer and co-host of the This Had Oscar Buzz podcast. His work has appeared in Decider, NPR, HuffPost, The Atlantic, Slate, Polygon, Vanity Fair, Vulture, The A.V. Club and more.

TOPICS: Cherries Wild, 30 Rock, America's Next Top Model, Community, Hawaii Five-0 (2010 series), Mad Men, Seinfeld, The Weakest Link, Advertising

- It Took a While, But Streaming Has Finally Embraced the Reality Competition

- Fox's Pepsi-themed game show Cherries Wild doesn't want to alienate Coke drinkers

- FOX's Witless Cherries Wild Is an Exercise in Product Integration — And Little Else

- Jason Biggs and the 30-Foot Slot Machine in Cherries Wild First Look