Helter Skelter: An American Myth Puts Epix on the Prestige True Crime Map

-

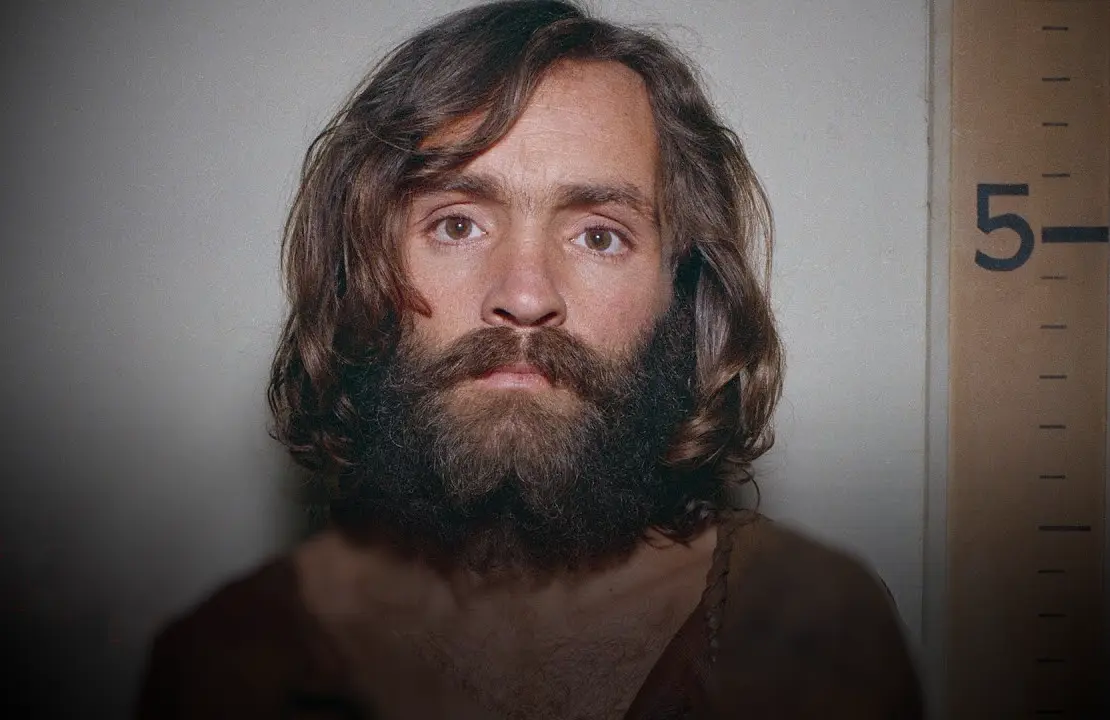

Helter Skelter takes yet another run at Manson. (Epix)

Helter Skelter takes yet another run at Manson. (Epix)Primetimer editor-at-large Sarah D. Bunting knows a thing or two about true crime. She founded the true crime site The Blotter, and is the host of its weekly podcast, The Blotter Presents. Her weekly column here on Primetimer is dedicated to all things true crime on TV.

This is a strange time to release a new docuseries on Charles Manson. For one thing, the fiftieth anniversary of the brutal crimes that made Manson a household name — the Tate and LaBianca murders — passed almost a year ago, accompanied by the usual barrage of programming and commentary that comes with such an anniversary (not to mention Quentin Tarantino's excellent "alternate history" of those days, Once Upon A Time...In Hollywood). For another, Epix's six-episode look at Charles Manson is called Helter Skelter: An American Myth, a reference to the race war Manson believed was coming as the sixties drew to a close (or, really, pretended he believed was coming in order to manipulate his followers). The Epix project was slated for a June 14 release, but was pushed back in response to the Black Lives Matter protests that sprang up after the death of George Floyd. An understandable move — but does Helter Skelter confront Manson's racist theories and paranoid manipulations in the context of the times? Or is it just a glossy, solemnly paced prestige property with little new to say about one of the twentieth century's most notorious crime figures?

While it's largely the latter, it's quite well done. The series enjoys an excellent pedigree: director Lesley Chilcott has, to date, primarily produced documentaries on climate change and girls in coding; elsewhere on the creative team, it's something of a WB reunion, with Greg Berlanti (Everwood, You) exec-producing and Buffy The Vampire Slayer composer Christophe Beck handling the score. Helter Skelter gets excellent access to case figures, including Manson followers Dianne Lake and Catherine Share; a juror from Manson's trial; Peter Coyote and his prayer beads; and author Jeff Guinn, who does a lot of insightful work in voice-over and talking-head interviews. The contemporary music and footage are well chosen, with a clear effort made not to recycle the same Buffalo Springfield track and Life magazine snapshots of Manson that we've heard and seen dozens of times. Helter Skelter creates an immersive sense of multiple times and places, from West Virginia in the 1940s, where Manson suffered a wretched childhood; to the Haight-Ashbury scene in 1967; to the summer of '69 in Los Angeles. Each episode is around an hour long, and well paced overall (although a few portentous chopper shots of L.A. traffic and smog could have been dropped to speed things up). It's well-researched and very watchable, even for viewers like me with advanced cases of Manson fatigue. If Epix is hoping to elbow its way into the premium-content conversation, Helter Skelter is a solid bet.

Still, I can't help thinking that the series misses some opportunities, that it's trying to be to Manson what OJ: Made In America was to the murders of Nicole Brown and Ron Goldman, a larger-context journey of everyone involved — victims, killers, even society — but it doesn't quite succeed. Naming the series Helter Skelter is perhaps more a reference to Manson-case prosecutor Vincent Bugliosi's seminal book than the "Helter Skelter" concept as Manson understood it, and if Manson only used "Helter Skelter" as a fear-mongering means of control over his followers, there's only so much you can say about the race-war theory... but it does seem appropriate to investigate why this particular method of string-pulling worked, and not some other scare tactic.

And if Helter Skelter is going to spend as much time as it does exploring how Manson came to be — the feckless mother, the abusive uncle, the inevitable institutionalization after years in reform school and prison, the Napoleon complex — it needs to bring Manson's victims forward to the same degree, and it doesn't. Rosemary and Leno LaBianca in particular tend to get overlooked in discussions about Manson, because they weren't Hollywood people or coffee heiresses. In one episode, it seems like Helter Skelter is about to focus on them — but instead turns its attention back to the sad, delusional Family situation in the desert. Sharon Tate and Roman Polanski don't get a ton of screen time either, and the idea that Manson's most loyal followers were also victims of a sort is discussed. But far more time is devoted to Manson himself. Which, as Guinn bitterly notes, is exactly how Manson wanted it. "He didn't just play us once," Guinn adds; Manson always gets us to talk about him in the end, and even with that observation logged on-camera, Chilcott gets conned in much the same way.

Helter Skelter might have benefited from a narrower focus — only the LaBianca murders; only the Manson Girls who showed up at the courthouse every day; only the jury — to keep Manson himself from pulling focus yet again. Or it might have benefited from going broader, giving us more context about segregated Los Angeles in the middle of the last century, going even deeper into the influence of the music business on Hollywood culture (and on Manson's aspirations). As it is, it's quite good, good enough that I wanted it to be even better. If nothing else, Helter Skelter's ambition bodes well for future docuseries from Epix.

Helter Skelter: An American Myth airs on Epix on July 26th at 10:00 PM ET

People are talking about Helter Skelter in our forums. Join the conversation.

Sarah D. Bunting co-founded Television Without Pity, and her work has appeared in Glamour and New York, and on MSNBC, NPR's Monkey See blog, MLB.com, and Yahoo!. Find her at her true-crime newsletter, Best Evidence, and on TV podcasts Extra Hot Great and Again With This.

TOPICS: Helter Skelter: An American Myth, Epix, Charles Manson, Greg Berlanti, True Crime