The Five Most Memorable Election Nights in TV History

-

Election Night on TV is a lot like the NFL Draft on ESPN — several hours of chatter, with occasional interruptions for breaking news. It can be very entertaining if you follow the game, really boring if you don’t. Yes, I know, “the future of our democracy” is not a game. I would point out, though, that it’s the peaceful transition of power that the future of our democracy actually hinges on. Election Night coverage is not a solemn rite of a republic, it’s reality TV.

Television began covering election results in 1948 and got a doozy of an assignment that night — four, count them four, major presidential candidates, and a margin of victory so Harry-razor-thin that several media outlets called the wrong winner. They waited 52 years before making that mistake again.

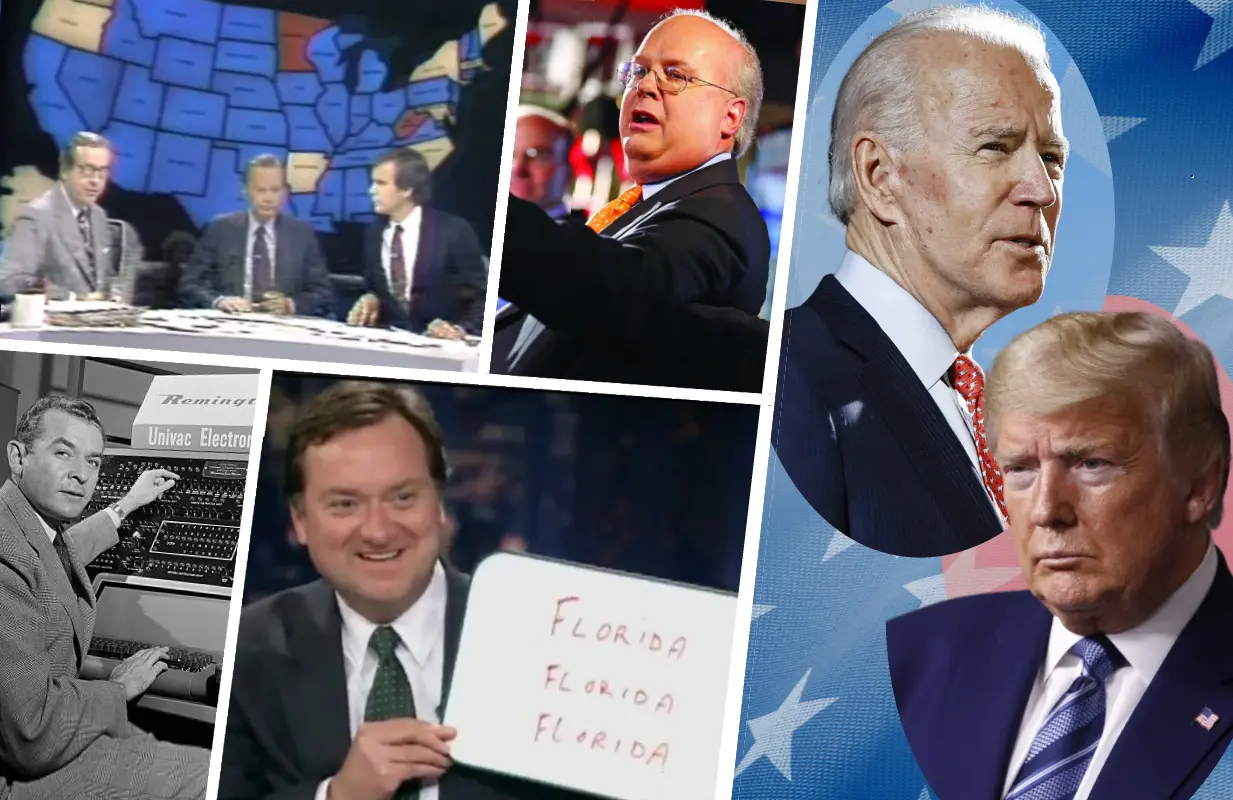

The first lighted electoral map made its debut on NBC in 1976, back when red meant Democrat and blue Republican. It was pretty, but more people remember Tim Russert scrawling on a white board during the Bush-Gore nail-biter in 2000.

The majority of election nights were long. Most were not very memorable. Here are five that were:

1948: Dewey Doesn’t Show

There was no way, no way, Harry Truman was getting elected president in 1948. His own party had split two ways — Henry Wallace leading the left into the Progressive Party, Strom Thurmond marching out of the Democratic Convention with his fellow Dixiecrats. That left a clear lane for Thomas E. Dewey, the smooth, pencil-mustachioed governor of New York, to be elected. The Chicago Tribune was so sure of this, it went ahead and splashed that result on its front page.

Radio was sure of the outcome, too. As Kansas Citians and Truman fans, we’ve made the pilgrimage to the Elms Hotel in Excelsior Springs, Mo., where Harry disappeared to early in the night, as radio announcers like H.V. Kaltenborn continued blathering on about Dewey’s impending win. At the hotel, Truman took a ham sandwich and some buttermilk, then went to bed. When he woke up, he had an insurmountable lead.

In 1948 TV was less interested in the outcome than in covering its first election. CBS and NBC barely had news divisions, and everything in their election coverage that night was wondrous and new. No one wanted it to end, so on it went for nearly 17 hours, until Ohio finally put Truman over the top.

Here’s a great piece of footage from NBC’s coverage from shortly after 11:00 AM ET on Wednesday. You’ll see DNC chairman J. Howard McGrath declare victory, and then NBC throws to New York’s Hotel Roosevelt for the loser’s concession speech. What viewers saw instead was several minutes of an empty stage festooned with bunting and a couple of sad banners declaring “Our Next President” and “Dewey.” Just off-stage, NBC correspondent Bob Stanton (actually a sportscaster) smoked a cigarette and vamped for time, since no one had a clue what was going to happen next. Obviously Dewey didn’t. A concession speech on TV? Who does that?

Back at 30 Rock, the three men anchoring NBC’s coverage were in heaven. “One of the great political pictures of all time,” one of them enthused. “The camera switched to that empty rostrum and there was nobody there but the American flag and emptiness!” Another agreed. “This is a marvelous news story!” And what about Harry? Unfortunately for TV, the AT&T video transmission line didn’t get to Kansas City until 1952 — so Truman’s victory speech was radio’s last hurrah.

1960: Battle of the Bots

The contest between John F. Kennedy and Richard Nixon was when democracy actually entered the television age. TV had a decisive role in the first-ever televised presidential debates — which, people seem to agree, Nixon won on the radio, but JFK won on TV — and while the two candidates would be battling it out all night in one of America’s closest presidential elections, the two major networks were also fighting for supremacy. As Stephen Battaglio relates in his enjoyable ebook on the 1960 election, the president of NBC told his news staff, “Men, you may think this election is a contest between Kennedy and Nixon. It’s not. It’s a race between NBC and CBS.” (ABC, the Jill Stein of its day, was a non-factor that night.)

It was also a battle between RCA and IBM, makers of the two dueling computer systems that would be trying to predict a winner first. Like the NBC suits who shut down Star Trek in the classic SNL sketch, David Brinkley and Chet Huntley looked like a couple of well-dressed stowaways on a spaceship, the RCA 501 and its hundreds of buttons and lights lining the back wall of their election studio. Over on CBS, a more familiar and comforting picture as Walter Cronkite presided over a wall of staffers on ladders, hand-posting election returns. It was poor Howard K. Smith, moderator of that famous first TV debate, who was assigned to the windowless basement where the IBM was kept.

NBC’s 501, Battaglio writes, “was the only computer to consistently predict Kennedy as the winner throughout the night, starting at 8:30 p.m. when it gave the Democrat 6.3 to 1 odds.” (Back then, people liked to play the horses.) At 3:15 a.m., Nixon appeared in front of a microphone, seemingly ready to give a concession address. But in a moment Al Gore would one day appreciate, he didn’t. Brinkley, for one, commended Nixon. “The election is not yet over,” he said. “Every time we look at it, it’s closer than the last time.” NBC finally called the race for JFK during the Today show.

1980: Media Voter Suppression

Jimmy Carter woke up on Election Day 1980 knowing he was going to lose to Ronald Reagan. The networks knew it, too. So why delay the inevitable? That was the thinking back then. NBC’s John Chancellor opened his network’s coverage at 6:30 p.m. ET by stating plainly, “Ronald Reagan will win a very substantial victory tonight. Very substantial.” Just two states had been called for Reagan at that moment.

A few minutes later on ABC, Barbara Walters shared with viewers a story from Carter’s pollster, who revealed that he had told the president the night before, “You’re going to lose.” CBS’s Walter Cronkite was a tad more conservative but still suggested a Reagan landslide early in the night’s coverage.

The problem was that polls were still open in the western United States when all this projecting occurred. And as a University of Michigan study revealed afterward, eligible voters in the west who had heard the election called for Reagan were much less likely to go vote than those who hadn’t heard the news, affecting a slew of downballot races.

Faced with congressional action, the networks made a voluntary policy change they’ve stuck to ever since — waiting until all the polls were closed before calling the presidential race, and for each state’s polls to close before calling any statewide elections there.

2000: Tune in Next Week

“This election is hotter than a Laredo parking lot,” is one of many, many Dan Rather aphorisms I remember from the endless night… that became a week… that became a Supreme Court decision. Because of what transpired after election night, the coverage was quickly forgotten, except for Tim Russert’s famous use of a white board and dry-erase marker in those glorious days before touch screens:

But Fox News, MSNBC, and CNN were on the scene in 2000 as well, and as it became clear the contest between Al Gore and George W. Bush would be too close to call, cable news would take over the story in the following days, marking the end of 40 years of network dominance of election coverage.

When I look at that night’s coverage with my nonpartisan hat on, it’s clear the journalists and experts on TV know this race had no business being this close. Bush won 11 states that had gone for the still-popular Bill Clinton just four years earlier. Forget Florida — if Gore had won his home state of Tennessee, he’d be president. CNN’s John King, proving his worth then as he has every single election since then, can be heard below at 1:14 AM ET quoting Democratic officials, who were already chirping about Gore’s lousy campaign strategy.

Television loves a great drama — hanging chads, 5-4 SCOTUS decisions — but in the end the 2000 election was probably a case of the candidate getting in his own way.

2012: Fox Calls It for Obama

There’s been a lot of malarkey being floated this election season, in my opinion, about whether the current president will “respect the legitimacy of the election.” To people who are losing sleep over the possibility that Trump will pull a Venezuela and simply not leave the presidential palace, I give you Fox News.

Yes, Fox’s endlessly hostile commentators can be annoying. And there was nothing fun about re-watching its coverage of Trump’s win in 2016 for this article. It reminded me of one of those parties where everyone starts out kind of tense and awkward, and by the end of the evening they’re dancing on the tables. But I will say this for Fox’s coverage: their numbers room is as fair as they get. In 2012 their team called Ohio for Obama, sparking outrage among the Romney camp and on-air contributor Karl Rove, who thought Fox had spoken too soon. So Megyn Kelly was dispatched to walk down to the numbers room and confirm the data on-camera:

In the end, Fox News may be our best guarantor of a smooth transition of power come January 20. It’s a news channel with a very large commentariat, but it does do news… way in the back of the building… and the election team is as aggressive as any network’s. They’ll want to call the winner before their competitors do. And if Trump sees Fox calling it for Biden, he can rage-tweet all he wants, but he’ll know — and we’ll know — that the jig is up.

Aaron Barnhart has written about television since 1994, including 15 years as TV critic for the Kansas City Star.

TOPICS: 2020 Presidential Election, CBS, CNN, Fox News Channel, NBC, Donald Trump

- CNN Boss Chris Licht Wants Staff to Stop Saying 'The Big Lie' (Report)

- Before Fox Business anchor Maria Bartiromo interviewed then-President Trump in November 2020, she texted her questions to his chief of staff Mark Meadows

- Voting technology company Smartmatic sues One American News and Newsmax

- Newsmax apologizes to Dominion Voting Systems employee who was subjected to 2020 presidential election conspiracy theories