Separating Fact from Fiction in Judas and the Black Messiah

-

Darrel Britt-Gibson, Daniel Kaluuya and Lakeith Stanfield in Judas and the Black Messiah. (Photo: Glen Wilson/Warner Bros.)

Darrel Britt-Gibson, Daniel Kaluuya and Lakeith Stanfield in Judas and the Black Messiah. (Photo: Glen Wilson/Warner Bros.)It’s been a helluva year for America, but it’s also been a hella great year for Black American cinema. And in a year when “the movies” meant whatever screen you could get your hands on, it’s fitting that the most important Black films were all funded by streaming TV channels: Ma Rainey’s Black Bottom and Da 5 Bloods on Netflix, The Banker on Apple TV+, Soul on Disney+, The United States Vs. Billie Holliday on Hulu, and All In, Time and One Night in Miami on Amazon Prime.

Judas and the Black Messiah now joins that impressive list. Like most of the others, it’s a slice of history that was hiding in plain sight, a story of Black struggle and progress happening parallel to — but largely excluded from — white American history. Written by brothers Kenny and Keith Lucas and debuting in theaters and on HBO Max February 12, Judas and the Black Messiah tells the story of one of the most disturbing chapters of American state-sponsored terrorism against its own people. As with these other films, it helps to know the history.

NOTE: Spoilers follow, so if you don’t know who Fred Hampton is or what happened to him, you may want to watch the film first.

The Black Panther Party

Though largely associated with Oakland, California, where it had a large and enduring presence, the Black Panther Party was actually started in Lowndes County, Alabama, during a voter registration drive in 1965. Lowndes County had a long history of white violence against its Black population, so when a group of militant civil rights activists, led by John Hulett and Stokely Carmichael, formed a political organization, they chose the fierce black panther as their emblem. By 1970 the party was organized in 68 cities, including Chicago, where this film takes place.

What separated the Black Panthers from other civil rights groups was its emphasis on Black power. Panthers led literacy and political education classes and organized other efforts to promote Black self-sufficiency. By 1969 Oakland’s Black Panthers had created the Free Breakfast for Children program and free clinics to treat diseases that were more common among Black Americans than whites.

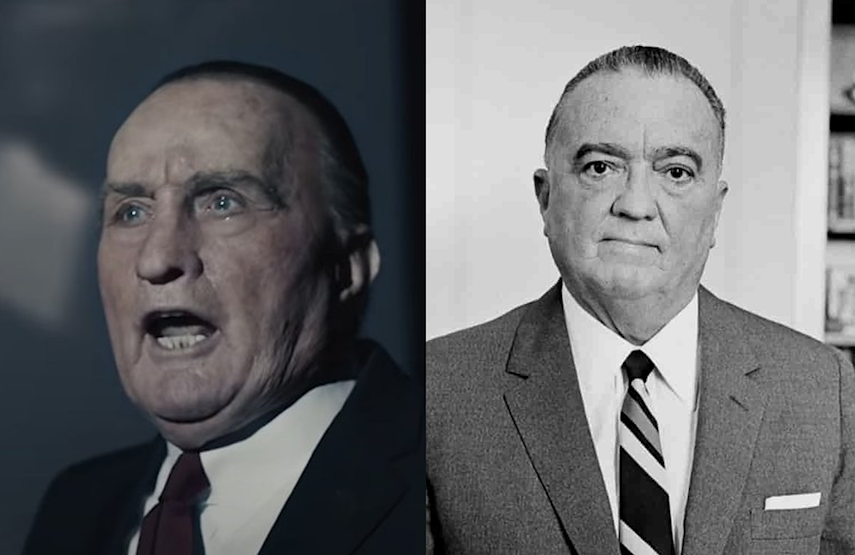

Eschewing the nonviolent approach of other civil rights leaders, the Panthers fully embraced their Second Amendment rights. “With the gun,” declared Oakland’s Huey Newton, Blacks could “recapture their dreams and bring them into reality.” Newton and fellow Panther Eldridge Cleaver got into a 1968 shootout with local police that left two cops and one Panther dead. From almost the get-go, the party found itself in the FBI’s crosshairs. Director J. Edgar Hoover declared the Black Panthers “the greatest threat to the internal security of the country” in 1969, the year the dramatic events of Judas and the Black Messiah unfold.

Fred Hampton

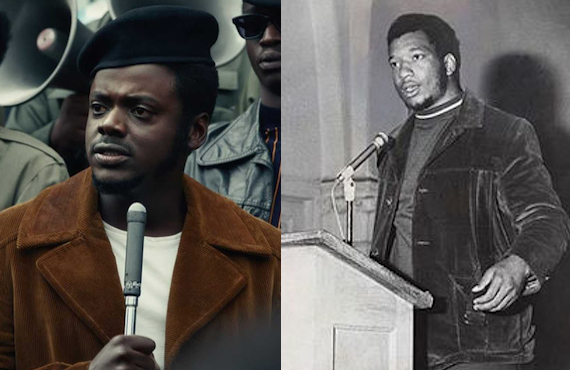

Played by Daniel Kaluuya, Fred Hampton was a bright progressive activist from a Chicago suburb when in 1968 he learned about the Black Panther Party, which by then had adopted its “Ten-Point Program,” a Marxist-flavored agenda for social action. Hampton moved to downtown Chicago and began an 18-month odyssey of protest and organizing that ended with his assassination by the FBI.

Unlike the Black Power movement of the mid-’60s, Hampton believed it was essential to work across racial lines to achieve a radical reboot of society. “When I talk about the masses, I’m talking about the white masses, I’m talking about the black masses, and the brown masses, and the yellow masses, too,” Hampton said in 1968. “We’re gonna fight racism with solidarity. We say you don’t fight capitalism with no black capitalism; you fight capitalism with socialism.”

A gifted and media-savvy speaker, Hampton was a rising star in both the Panther Party and Chicago politics. He had the trust of the Young Lords, the city’s largest street gang, and was able to broker a truce between the Lords and other gangs.

J. Edgar Hoover

Played by the indomitable Martin Sheen, FBI director Hoover successfully infiltrated dozens of chapters of the Black Panther Party across America, including the one in Chicago. These spies fomented division wherever possible, leading to a bitter split among the Chicago group’s leadership in 1969. After Hampton took control of the Black Panther Party in Illinois, the FBI stepped up its surveillance of him, with the support of Mayor Richard J. Daley’s Chicago police, who had arrested Hampton at the 1968 Democratic Convention in that city, making Hampton an indicted co-conspirator at the Chicago 7 trial.

William O’Neal

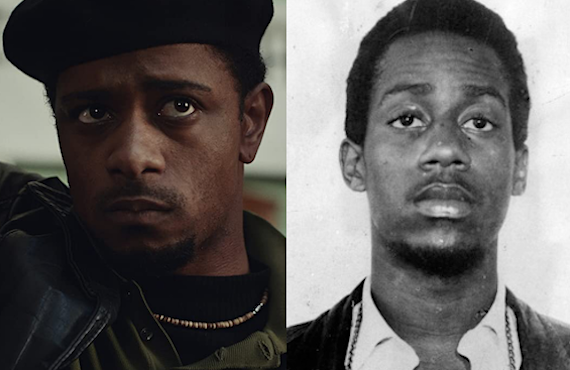

The white-dominated FBI couldn’t do it alone, of course. The Bureau needed Black men as informants inside the Black Panther organization. In Chicago no one was more helpful to Hoover than William O’Neal, the “Judas” in the film’s title. Played by LaKeith Stanfield, O’Neal was a 17-year-old knucklehead with a long rap sheet when the FBI pulled him over in a stolen car in Michigan. In exchange for avoiding federal charges, O’Neal agreed to infiltrate the Black Panther Party. He soon earned Fred Hampton’s confidence and became a trusted member of Hampton’s security team.

Thanks to O’Neal, a heavily armed Chicago police squad was able to break into Hampton’s apartment on the morning of December 4, 1969, and assassinated him as he slept, along with a lieutenant, Mark Clark (played by Jermaine Fowler). In a press conference afterward, Chicago police declared the raid had actually been a “shootout” and presented evidence of bullet holes from a gun allegedly fired by Hampton. Six weeks later, on January 21, 1970, an inquest declared that the killings had been “justifiable.” It would take years of independent investigations to get to the truth and a multi-million-dollar settlement with survivors.

Bobby Rush

As with every political star cut down in their prime, observers have speculated how history might have been different had Fred Hampton lived. Would thousands of Black men been spared violent deaths and long jail terms and led a political revolution in Chicago? One tantalizing answer to that question comes in the form of Bobby Rush, played by Darrell Britt-Gibson (“O-Dog” from The Wire). A co-founder of the Chicago chapter of the Black Panthers, Rush assumed leadership after Hampton’s killing. “Black people have been on the defensive for all these years,” he declared. “We advocate offensive violence against the power structure.”

By the early 1970s, however, Rush was having a change of heart. He devoted himself to community organizing and by 1974 had quit the Black Panthers, a party decimated by FBI-sowed infighting and criminal activity. He found Jesus but never repudiated his time in the Panthers, calling it “part of my maturing.” In 1992, Rush was elected to Congress and served ten terms, easily turning back a young challenger named Barack Obama in the Democratic primary in 2000.

Though the dialogue in Judas and the Black Messiah is fictional, the screenplay has the blessing of Hampton’s survivors and is considered historically sound. If you want to learn more about the events depicted in the film, spend two bucks and rent Howard Alk’s 1971 documentary The Murder of Fred Hampton. Alk took his camera inside the apartment where Hampton was gunned down, offering an entirely different version of events than had been advanced in the media by the police and FBI. For another dramatic treatment of events that preceded those of Judas and the Black Messiah, watch The Trial of the Chicago 7 on Netflix.

Judas and the Black Messiah premieres on HBO Max February 12th, where it will screen for a month.

Aaron Barnhart has written about television since 1994, including 15 years as TV critic for the Kansas City Star.

TOPICS: Judas And the Black Messiah, HBO Max, Daniel Kaluuya, LaKeith Stanfield, Martin Sheen