Fargo Season 4 Is a LOT — Too Much, Actually

-

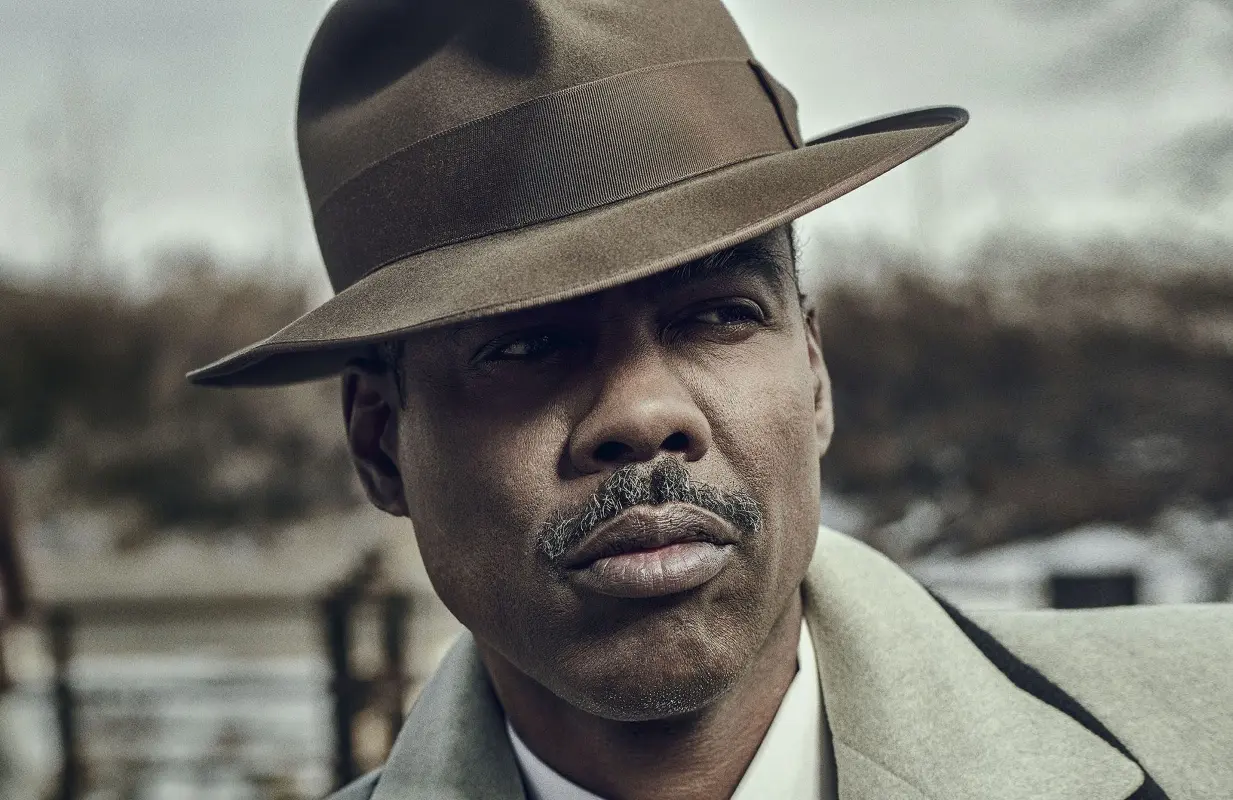

Chris Rock stars as a Kansas City gangster in Fargo Season 4. (FX)

Chris Rock stars as a Kansas City gangster in Fargo Season 4. (FX)Crime sagas have long been used as a vessel for exploring the social fabric of America. Since James Cagney's The Public Enemy and the original Scarface established the templates for the American gangster, up through The Godfather trilogy, Goodfellas, and HBO's The Sopranos, stories of American enterprise and family have played upon the idea that you take what you can, because nobody is going to give it to you. It was and is a coarse and bloody conception of how to succeed in America, but it's one that's endured for nearly a century on the screen. The Coen Brothers have explored this territory often, almost always with arched eyebrows, telling the stories of criminal enterprises undone by selfishness, incompetence, or simple fate.

In choosing to adapt the Coens' 1996 criminal opus Fargo, Noah Hawley has told various stories of villainy set beneath the supposedly quaint facade of midwestern friendliness. For Fargo's fourth season, he's moved things to a setting less bound by the Minnesotan pleasantries that have made the violence of past seasons so startling. With a mob war between Italian and Black factions in 1950 Kansas City as its backdrop, this new season is more straightforward with its themes — particularly America's deeply rooted racial sins — at the same time retreating to more stereotypical crime-fiction ground. The end result can at times get a bit lost in its own plotting. "You want to know why America loves a crime story?" asks one mobbed-up character. "Because America is a crime story." This is as close as Fargo Season 4 comes to a coherent thesis, but it's one that's broad enough to encompass virtually all American crime fiction for decades.

The somewhat fact-based backstory for the season is the history of organized crime in 20th century Kansas City, where an immigrant Jewish faction gives way to an immigrant Irish faction, which gives way to an immigrant Italian faction. Preceding each violent transfer of power, the two competing concerns would make a trade: the youngest sons of the family in power would be swapped, the idea being that peace could be maintained if the families knew their most vulnerable kin would be killed if the families went to war. But in Hawley's telling, these truces are violated without exception, with the new family inevitably mowing down the old one in a hail of bullets, often with the traded youngest son as either a spy or a traitor. So when we reach 1950, and the powerful Italian Fadda family squares off with Chris Rock as the head of the Cannon organization, their trade of youngest sons doesn't hold all that much suspense to it. We know there's going to be a war, and we know these sons will be targets; it's only a matter of time. (And yes, Hawley did decide to name his two central families Cannon/Fadda. Much like his decision to kick off the scenes from previous episodes with "antecedently on Fargo," such wordplay comes off as cleverness for cleverness' sake, and never really pays off.)

Chris Rock stars as Loy Cannon, the head of a crime family that's moved to Kansas City to get out of the Jim Crow south. He makes the aforementioned uneasy agreement with the Fadda family, which immediately begins to crumble via a typically Fargo-ian combination of mistrust and fateful misadventure. The heir-apparent sons of the Fadda clan present the biggest problem: Josto (Jason Schwartzman) is your classic pampered son of criminal privilege: pompous and erudite, full of loud threats and barely-veiled insecurity. He's also, you know, played by Jason Schwartzman, who has never been able to keep his essentially bratty Millennial vibe at bay. His brother, Gaetano (Salvatore Espositio), was raised in Sardinia, in Mussolini's Italy, and is a hardened maniac of a man. The two brothers clash and immediately begin jockeying for power.

That's not all, of course — not by a long shot. Personalities speckle the show's vast canvas, from Loy's standup consigliere, Doctor Senator, played with charismatic authority by Glynn Turman, to Rabbi Milligan (Ben Whishaw), who plays the swapped Irish son of the last criminal regime who betrayed his family and has taken up the care and protection of Loy's youngest son, now living with the Faddas. And that's not even getting into the Smutney family, white Thurman (Andrew Bird) and his Black wife Dibrell (Anjie White), who operate a funeral parlor out of their home. Their teenage daughter Ethelrida (E'myri Crutchfield) is actually the narrator of this whole season, despite her being entirely outside the sphere of the mob war. But wait! There's also the angel-of-death murderous nurse Oraetta Mayflower, played by ascendant Irish actress Jessie Buckley, giving the show its requisite dose of heavy Minnesotan accent, who keeps murdering patients and anyone who might be close to catching on to her. And then we mustn't forget Dibrell's sister, Zelmare Roulette, played by Karen Aldridge . Zelmare and her beloved Swanee Capp (Kelsey Asbille) are prison-escapee bandits, a Bonnie & Bonnie pair, looking to rob their way through life, whose moral alignment with the rest of the season is constantly in flux, and who also see ghosts. They are being pursued by a Mormon U.S. marshal, played by Timothy Olyphant (who last played a U.S. marshal on FX's Justified). And he's partnered with a crook played by Jack Huston, perhaps best known for Boardwalk Empire, the show that this season most reminds me of, particularly in the way that both series' criminals love to deliver long monologues before inevitably shooting someone.

If this all sounds wildly overstuffed for a mere eleven episodes of television, indeed it is. The appeal of a story told on this scale is that the whole enterprise can feel like a lived-in portrait of a community, telling the story of America through the warring factions in this one particular town. But Fargo isn't meant to feel lived-in, and this season in particular feels like pieces from different puzzles all mashed together into a portrait that's supposed to be breathtaking in its sweep, but instead ends up being alternately ponderous and exhausting. It doesn't help that the acting is all over the place, with Schwartzman and Rock and their way-too-contemporary vibes clashing with Buckley and Olyphant shooting for the broad side of a barn with their performances. Only Whishaw, as Rabbi Milligan, manages to wring any real pathos from his role. It should probably be noted that "Milligan" was the surname of Bokeem Woodbine's character — a Kansas City mobster — in Season 2, and given the show's penchant for stringing its seasons together in some way, you can probably expect that thread to tie up by season's end (critics were given the first nine of the eleven episodes).

All told, Fargo's ambitions are admirable, but in trying to tell a story about Black entrepreneurship undone by racism and violence in the middle of America, it groans and wheezes under the weight of far too much sound and fury coming from all corners.

Fargo Season 4 premieres on FX with back-to-back episodes September 27th at 10:00 PM ET

People are talking about Fargo in our forums. Join the conversation.

Joe Reid is the senior writer at Primetimer and co-host of the This Had Oscar Buzz podcast. His work has appeared in Decider, NPR, HuffPost, The Atlantic, Slate, Polygon, Vanity Fair, Vulture, The A.V. Club and more.

TOPICS: Fargo, FX, Chris Rock, Glynn Turman, Jack Huston, Jason Schwartzman, Jessie Buckley, Noah Hawley, Timothy Olyphant