Hulu's Dopesick Is a Hokey, Overlong Morality Play That Everyone Should Watch

-

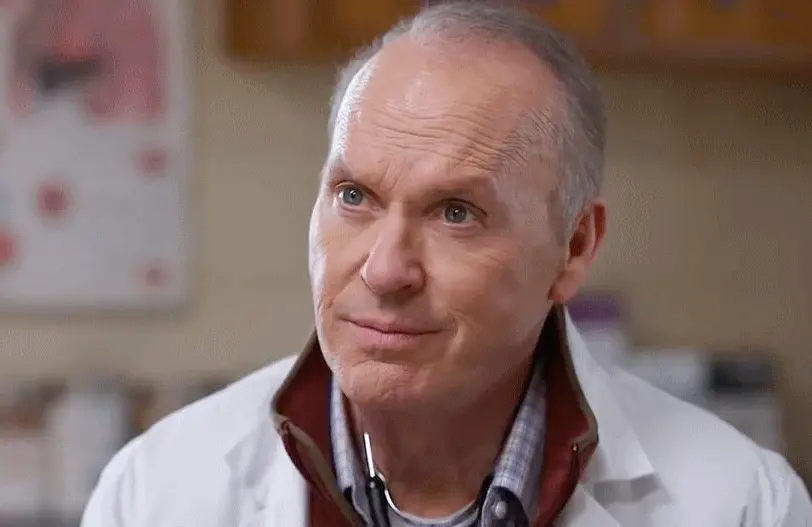

Michael Keaton plays kind-hearted country doctor Samuel Finnix, an unknowing accomplice to Purdue Parma in Dopesick. (Photo: Hulu)

Michael Keaton plays kind-hearted country doctor Samuel Finnix, an unknowing accomplice to Purdue Parma in Dopesick. (Photo: Hulu)One of the amazing signs of human resilience is how many of us manage our days despite chronic pain. Millions, in fact, are unable to work or function in everyday life without heavy-duty painkillers. I’ve experienced this level of agony once in my life, and it put me in the hospital for three months. Fortunately, we got the pain under control without having to resort to opioids. Many are not so lucky; they have my sympathy and respect.

For years Vicodin and Percocet were the opioids of choice for people desperate to dull their chronic pain. (Dr. House, you’ll recall, ate Vicodin pills like they were Tic Tacs.) And then along came OxyContin. It was the “safe” opioid, because it had a 12-hour time release formula. OxyContin was released to the market in 1995, and whatever its virtues for those suffering chronic pain, safety was not one of them. Soon reports of rampant addictions, folks crushing the pills to make “hillbilly heroin” and thousands of overdoses began surfacing in rural America, where OxyContin was heavily prescribed.

In recent years one especially bad actor has been in the news for perpetuating this disaster of drug abuse and death: Purdue Pharma, the maker of OxyContin, which aggressively marketed the drug for over a decade. OxyContin made billions of dollars in profits for the Sackler family, owners of privately-held Purdue, and they used their wealth to endow museums and many other worthy causes. But the Sacklers have long since disappeared from view, as has their name from the buildings they paid for, and the family is winding up a massive settlement resulting from lawsuits by states’ attorneys-general and the federal government, who hold them largely responsible for many, if not most, of the 200,000 deaths from opioid abuse in the U.S.

Purdue and the Sacklers are the designated villain in Dopesick, a new eight-part series from Hulu that tells the story of the opioid epidemic and the role of OxyContin in accelerating it. Using composite characters and speculative dialogue, the Hulu series tells a dramatized version of events that were originally reported by Beth Macy for the New York Times and her 2018 nonfiction bestseller, Dopesick: Dealers, Doctors, and the Drug Company That Addicted America. The program’s eight-hour length, star power — Michael Keaton, Peter Sarsgaard, Kaitlyn Dever and Rosario Dawson are among the cast's many heavyweights — and strong promotion gave every reason to believe this would be a television event on the order of Hulu’s last big thing, the charming Steve Martin mystery Only Murders in the Building.

By that measure, Dopesick disappoints. It is nowhere near as well-written or well-acted. It verges at times on hokey melodrama, pitting the innocent victims of OxyContin and heroic federal law enforcers against the evil Sackler family (played by lesser-known actors), who obviously have no concern for the carnage their product is causing — all they care about is return on investment.

Also, the show is too damn long. It might be the most extreme case of episode bloat I’ve seen. Huge portions of Dopesick are spent developing storylines that have little or nothing to do with the opioid crisis. There are romances and family dramas and personal crises and tragic accidents. After a while I started to suspect that executive producer Barry Levinson and writer Danny Strong had been put under strict orders from Hulu: Whatever you do, make it eight hours.

So, yes, I’m disappointed. But I'm recommending Dopesick anyway, because quite honestly I don’t think the show was designed for a viewer like me. I don’t need to watch a heavy-handed melodrama about opioids because, in my hour of need, I did everything I could to avoid them. I remembered what happened when my wife was once prescribed a small amount of Vicodin. For the next three weeks she was like Miles Davis trying to get off the junk.

With all of the time I’ve spent inside the medical-industrial complex — where, to be clear, a cutting-edge chemotherapy regimen saved my life — I’ve developed a healthy irreverence toward what people in white coats tell me. They don’t know everything but they’re awfully good at talking like they do. What they don’t say is that a multi-billion-dollar industry exists with the sole intent of influencing doctors, nurse-practitioners and related healers to prescribe their products. When you hear a TV announcer urging you to “ask your doctor” about a drug that costs $40,000 a month, that ain’t a public service announcement.

The star of Dopesick, Michael Keaton, plays a kind-hearted country doctor working in Coal Country. He's the kind of doctor who pays a house call to make sure one of his patients is taking her pills. Thanks to a flash-forward early in the first episode, we know that Doc Keaton will one day testify before a congressional committee about all the OxyContin scripts he wrote over the years. Thus we already know that Purdue will co-opt this caring physician. The only mystery then is, how did they do it?

Rewind to the early 1990s. (Dopesick does a lot of moving back and forth on the timeline. Get out the Dramamine.) Purdue hired hundreds of sales reps who fanned out to working-class, mostly rural areas of America where they felt the OxyContin pitch would be well-received. They went to a playbook that all of us recognize today from those commercials on TV: first create awareness around the problem, then offer the solution.

Purdue poured millions into raising awareness about the problem of “breakthrough pain,” and funded soft influencers like the Appalachian Pain Foundation, groups that held academic conferences to roll out white papers that suggested making pain “the 5th vital sign.” Trusted country doctors were invited to these shindigs, wined and dined, made to feel special and that someone was listening to them.

And the reality is that these doctors were getting an earful from their patients about their pain issues.“Breakthrough pain” may have been the marketing department’s way of expressing it, but marketing exists for a reason — it makes the complex simple, and sellable. Purdue knew that Medicare was starting to punish hospitals that didn’t score highly in patient-satisfaction surveys, and that doctors were under increasing pressure to send home patients pain-free. All of this is dramatized in an ongoing storyline involving our good-hearted Doc Keaton, who is doted upon by his local Purdue rep and invited to a Purdue-funded conference.

Elsewhere in Coal Country, an FBI agent (Sarsgaard) is disturbed by the growing body count from opioid abuse. He and his partner soon figure out the game Purdue is playing, and try to get Washington interested. FBI director James Comey is puzzled why one of his field officers is “investigating the chicken guy.” (Uh, that would be Frank Perdue with an “e,” sir. By the way, that really happened.) Eventually, a DEA agent played by Dawson gets interested in the case, and the long, tedious process of reeling in the Sacklers begins, but thousands more will die before there is a reckoning.

Even today, the FDA’s ongoing investigation confirms that opioid abuse is still a huge problem (though mostly fentanyl these days; OxyContin peaked about 10 years ago). Addictive painkillers are still being overprescribed and not just by a few careless or reckless physicians. Dopesick follows the money, in a rather stomp-footed way, back to the people whose expensive marketing campaigns kick-started this epidemic of abuse. Hulu has apparently decided that this adaptation of a nonfiction book should resemble a very long movie-of-the-week. But you know, a lot of people like to watch those — people who wouldn't click on a documentary on the same subject, even one as compelling as Alex Gibney’s Crime of the Century (which is half as long as Dopesick). They don’t care that it’s hokey, or that Richard Sackler is a drama queen who refuses to take a day of vacation until OxyContin is available in every drugstore on the planet. They’ll like that Sarsgaard’s character prays. They’ll cheer when Dawson’s character finds her soulmate. They’ll care that Dever’s character has had her young, sweet life ruined by opioids. And if they get pulled into Dopesick’s story, then maybe they, too, will follow the money.

Dopesick premieres on Hulu Wednesday October 13th. New episodes are set to be released weekly through November 17.

Aaron Barnhart has written about television since 1994, including 15 years as TV critic for the Kansas City Star.

TOPICS: Dopesick, Hulu, Kaitlyn Dever, Michael Keaton, Peter Sarsgaard