In HBO’s Longford, Evil and Redemption in the Age Before Mass Incarceration

-

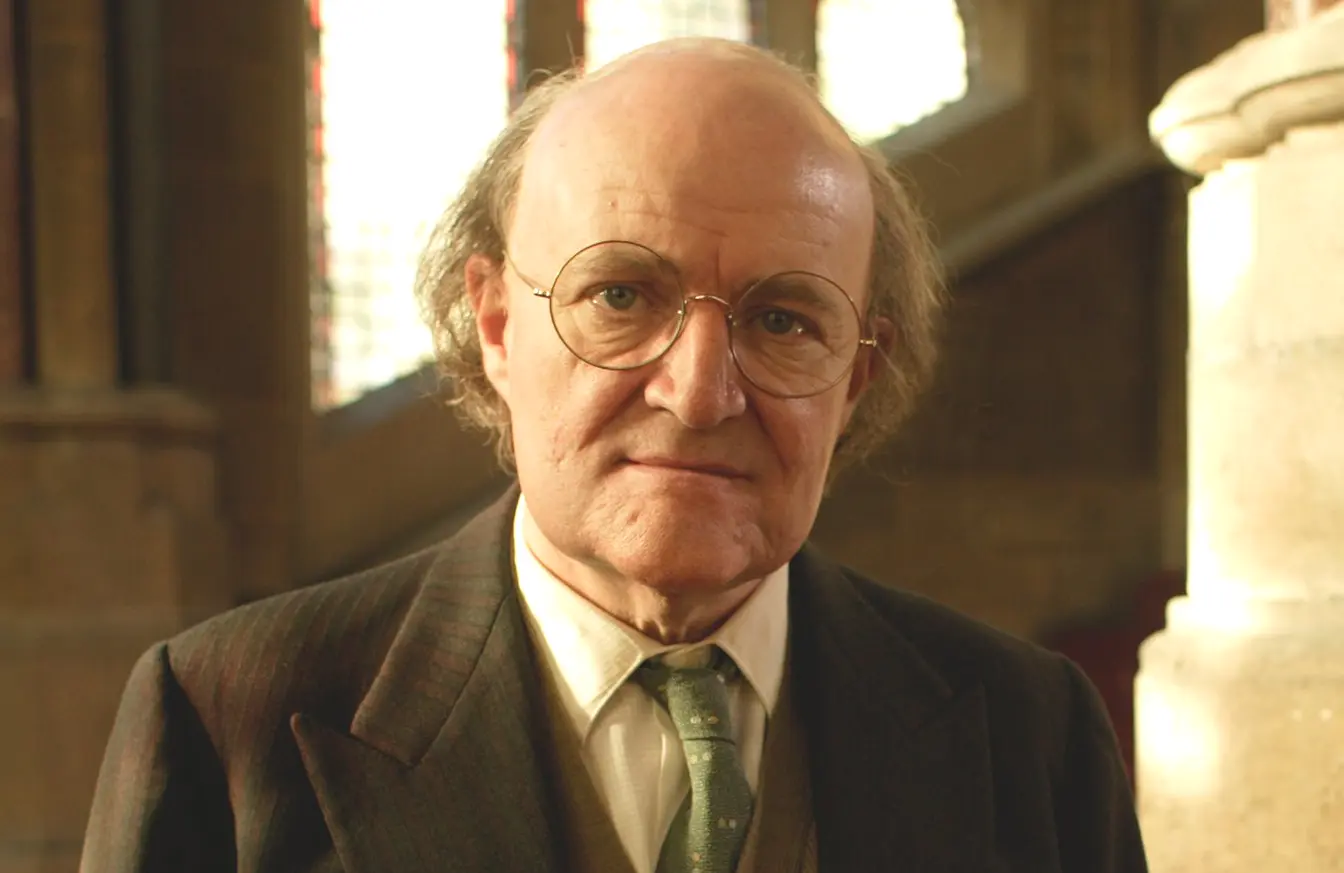

Jim Broadbent stars as the 7th Earl of Longford, a portrayal which earned him both a Golden Globe and BAFTA. (Photo: Giles Keyte/HBO)

Jim Broadbent stars as the 7th Earl of Longford, a portrayal which earned him both a Golden Globe and BAFTA. (Photo: Giles Keyte/HBO)Longford

2006

Watch on HBO GO | Rent or Buy on YouTube | Netflix DVDThere was a time during Peter Morgan’s ascent to the upper echelon of screenwriters when he would take on a project because it was worth doing, even if it couldn’t be sold to American audiences. In 2006, a full decade before he created The Crown, and a year in which crowds were flocking to movie theaters to see Helen Mirren as The Queen (which he wrote), Morgan turned out a little gem called Longford for HBO and Britain’s Channel 4.

The story concerns a minor footnote in British history, a tabloid scandal from the 1970s involving a Catholic do-gooder and a child murderer. Yet Longford turns out to have something surprisingly powerful to say about the world we live in now. This quietly powerful character drama about evil and redemption resonates in an age of mass incarceration.

The great Jim Broadbent stars as Frank Pakenham, aka the 7th Earl of Longford, an earnest if eccentric crusading 20th-century politician who championed many causes over his long public career, none more durably or productively as criminal justice reform. Longford, a devout social-justice Catholic, visited and befriended thousands of prisoners from the 1950s until his death. He pioneered efforts to reintegrate convicts into society after their release. He thought even murderers capable of redemption and of returning to productive lives outside prison.

If all of this makes him sound slightly saintly, a bit above the rest of us, he wasn’t. Broadbent convincingly portrays Longford as warts-and-all activist who leaned into everything his heart told him to, even when his head might have told him otherwise. No case demonstrated this better, or came closer to ruining him, than his long-running campaign to exonerate Myra Hindley.

Played to chilling perfection by Samantha Morton, Hindley was convicted for her role in a series of child murders that shocked Britain in the 1960s. The stench of the case hung over Manchester for decades, leading the city council in 1987 to authorize demolishing the house where Hindley and her co-defendant, Ian Brady, had lived, citing “excessive media interest creating unpleasantness for residents.”Yet for years Longford met privately with Hindley, convinced that she could be reformed and returned to a life outside prison. When their relationship was leaked to the press, he doubled down, not only continuing to see her but publicly declaring his intention to seek Hindley’s early release, a stance that brought record levels of opprobrium raining down on him.

In the film, Morgan plays out their relationship in nuances that were simply beyond the ability of Fleet Street newspapers to grasp. We see Longford straining to believe the best about Myra, especially in the face of all the blowback. Myra, meanwhile, can’t figure out why this member of the House of Lords would want to be her champion, and remains wary of Longford. The frisson between the accused killer and her very public defender keeps us on continuous edge until the film’s explosive climax.

Morgan leavens his script with scenes from Longford’s strong marriage to Elizabeth (Lindsay Duncan), a woman both clear-eyed about the world and devoted to the unusual man she married. For a time Longford was better known for his role on a commission studying the effects of pornography. The amusing effects this has on his life with Elizabeth serves to lighten the mood of what is basically a televised play about human depravity.

Morgan’s ability to capture the excitement of a time through both public and private interactions (something he also did in Frost/Nixon) helped me connect the story of Longford to our current crises involving prisons. There’s been a lot of sympathy of late extended to refugee families who have been manhandled by an incompetent border control system, and rightly so. But there are hundreds of thousands of people idling needlessly in prisons located within our borders. Who is thinking about them, visiting them, countering the narrative that they are monsters, losers, creatures unworthy of inclusion in a free society?I should add that Longford did not go entirely overlooked in the U.S. It was nominated for four Emmy Awards, and took home more Golden Globes that year than any other TV program, including Mad Men. Because of a writers’ strike, however, NBC didn’t air the Golden Globes — and since that is the only time of the year when Americans pay attention to the foreign press, Longford was promptly forgotten on our shores.

But it is still out there in the vast on-demand universe, and still worth watching. Indeed, as a character drama focused on perceived miscarriages of justice and the lone wolves who take up unpopular causes, Longford pairs nicely with Rectify, which I revisited in an earlier edition of The Overlooked. And anytime the criminal-justice system comes up, I feel compelled to remind you that 13TH is probably still moldering in your watchlist; you’d best watch it soon.

Aaron Barnhart has written about television since 1994, including 15 years as TV critic for the Kansas City Star.

TOPICS: Peter Morgan, HBO, Longford, Jim Broadbent, Samantha Morton