NASA’s Hubble Telescope observations reveal repeated asteroid collisions in a nearby planetary system

-

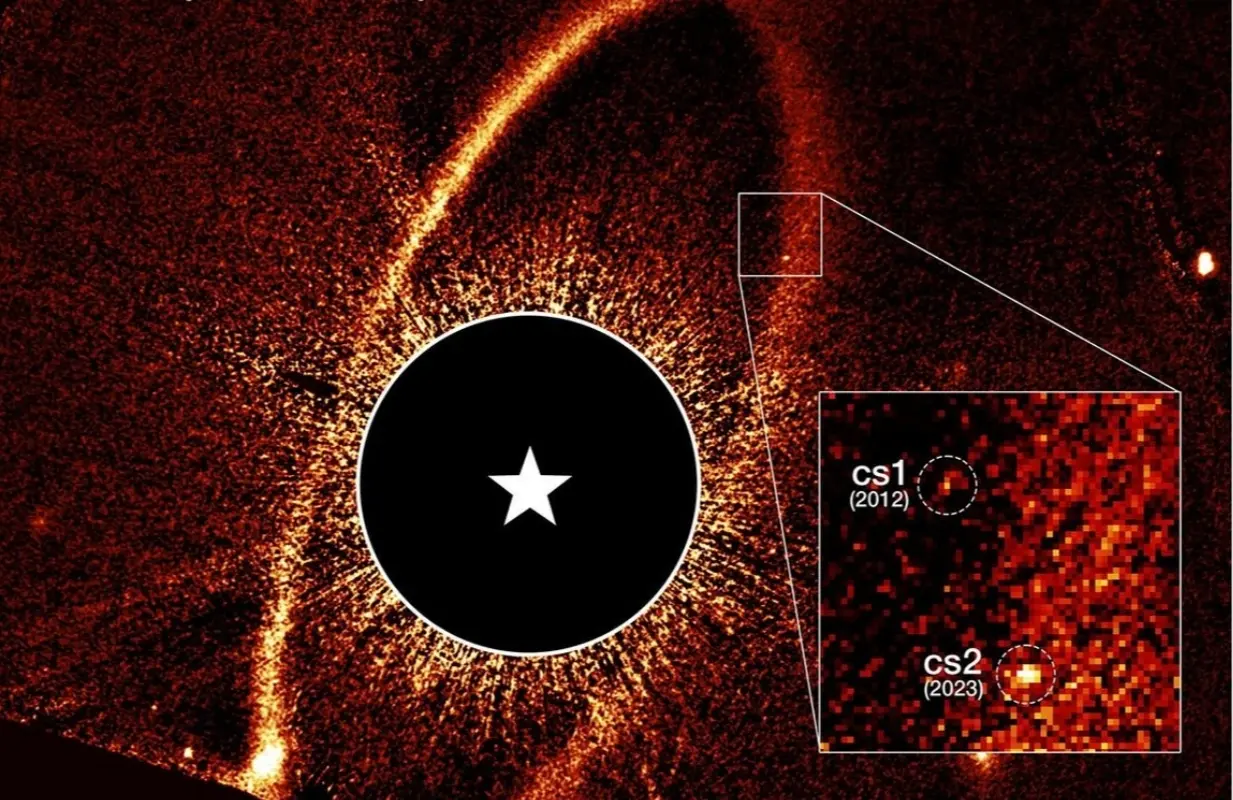

This composite Hubble Space Telescope image shows the debris ring and dust clouds cs1 and cs2 around the star Fomalhaut (Image via NASA)

This composite Hubble Space Telescope image shows the debris ring and dust clouds cs1 and cs2 around the star Fomalhaut (Image via NASA)NASA’s Hubble Space Telescope has recorded repeated collisions between asteroids in the planetary system surrounding the star Fomalhaut, located approximately 25 light-years from Earth in the constellation Piscis Austrinus.

Observations show two separate debris clouds resulting from high-energy impacts between large planetesimals, now identified as circumstellar source 1, or cs1, and circumstellar source 2, or cs2.

These collisions were detected during a search for the previously identified object Fomalhaut b, which had been thought to be a planet but now appears to be the product of a prior collision between planetesimals.

The findings confirm that catastrophic collisions are occurring within this system and provide measurable data on the size and distribution of its debris, according to NASA and scientists at the University of California, Berkeley, and the University of Cambridge.

Repeated asteroid collisions observed in the Fomalhaut System by NASA’s Hubble Telescope

Identification of colliding debris clouds

In the recent Hubble observations, cs1 and cs2 were both identified in proximity along Fomalhaut’s outer debris disk.

Cs1 was previously observed as Fomalhaut b in 2008, but analysis determined it is a dust cloud rather than a planet. Cs2 appeared as a new point of light not present in earlier Hubble images.

The alignment of cs1 and cs2 in the same region of the debris disk is unusual, given that theoretical models predict collisions between asteroids and planetesimals to be random.

Researchers recorded these events within a short timespan of approximately 20 years, whereas models had previously suggested a single collision might occur once every 100,000 years.

The repeated collisions allow astronomers to study the dynamics and frequency of such events in a planetary system outside the Solar System.

Characteristics of the colliding objects

Observations reveal that the planetesimals that led to the formation of cs1 and cs2 were about 37 miles or 60 kilometers in diameter.

Calculations from the debris disk put the number of such objects in the Fomalhaut system close to 300 million, all around the same size.

The Hubble data give the clouds’ location, brightness, and changes over time, thus allowing the sizes of the colliding bodies and their distribution in the disk to be worked out.

This is essential information for simulations of planetary debris dynamics and determining the physical aspects of planetesimal collisions in exoplanetary systems.

Monitoring and future observations

The Hubble team has been given a time slot for observations to follow cs2 changes over three years.

The researchers want to see how the shape, brightness, and orbital path of the cloud will change to figure out the interactions with the other matter in the Fomalhaut debris belt.

They are also planning to make some more observations with NASA’s James Webb Space Telescope, especially with its Near-Infrared Camera (NIRCam), to find out the composition and the size of the dust grains in cs2 and if there is any water ice.

While Hubble is getting data in the visible part of the spectrum, Webb’s infrared capabilities offer measurements that are necessary for a multi-spectral study of the system.

Implications for exoplanet studies

Transitory dust clouds like cs1 and cs2 could potentially be mistaken for exoplanets in reflected light, which means that upcoming space missions need to consider the possibility of such events.

Settings of Fomalhaut reveal how dust clouds become long-lasting and continue to reflect starlight for quite a while.

Ongoing observations by Hubble and Webb serve as a tool to tell the difference between real planets and ephemeral dust clumps in the debris disks of stars.

The results were published in the December 18, 2025, issue of the journal Science. Hubble Space Telescope is a collaborative program of NASA and ESA.

NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center takes care of mission management. Support comes from Lockheed Martin Space, and scientific operations are handled by the Space Telescope Science Institute.

Stay tuned for more updates.

TOPICS: NASA Hubble Space Telescope, exoplanet debris clouds, Fomalhaut planetary system, Hubble observations 2025, James Webb Space Telescope NIRCam, NASA, NASA asteroid collisions