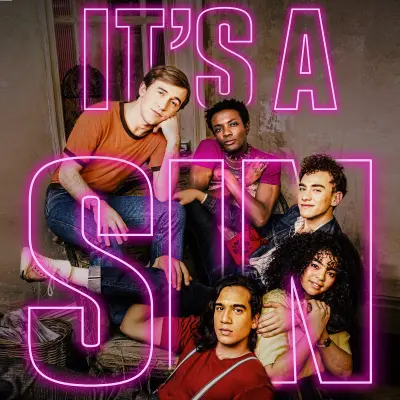

Russell T Davies' It's a Sin finds love and joy amid the sadness and shame of the AIDS crisis

-

"After being steeped for so long in so much sadness and shame, it can feel audacious to acknowledge that happiness and love and joy still existed during the AIDS crisis, and that they were just as important as the fear and death," says Alex Abad-Santos of Davies' five-part HBO Max limited series that originally aired on Britain's Channel 4 earlier this year. "That rare, audacious acknowledgment is integral to It’s a Sin, a moving, five-part coming-of-age miniseries from screenwriter Russell T. Davies (Queer as Folk) that premieres February 18 on HBO Max. Davies places equal emphasis on the joy and pain, declaring that we can’t possibly fathom the immensity of what the AIDS crisis destroyed if we ignore the happiness and love that gay men created for themselves. Over the course of the series, death finds its way into our protagonists’ lives but does not stop them from falling in love or falling out of it, from escaping the crisis and being pulled back in, from finding friendships even as their friends disappear. The men at the center of this story must also come to terms with the inexplicable luck of surviving. And through it all, Davies reminds us that although the AIDS crisis took so much, its victims did not live — and did not die — lonely." Abad-Santos adds: "The series’ five episodes — each one’s about an hour long — largely unfold in chronological order, sometimes leapfrogging a year or two, to eventually end in the early ’90s. This means that in every moment of every year we see onscreen, we know more than our heroes do about the horror that’s started to befall them, and the horror that is still to come. When one of the characters shrugs off an article in the paper about a mysterious cancer, it puts viewers in an emotionally helpless situation, like watching someone turn their back to a shark...The effect is devastating and crushing, because for as good as It’s a Sin is at depicting excitement and joy, it’s equally adept at showing the cruel randomness of the disease. There’s no rhyme or reason as to which characters contract AIDS and which ones don’t. Dumb luck comes with inescapable survivor’s guilt. The only constant is the inevitability of death once you contract it. When AZT, the first effective anti-HIV drug, is approved for use in 1987, some of the characters on the show have already died, years earlier. That said, the series doesn’t strive to present a very specific historical retelling — it’s more of a period piece."

ALSO:

- It's a Sin gets the big, emotional moments and moral arguments right: "The pitfalls and clichés of AIDS narratives are many," says Judy Berman. "It’s easy to unwittingly punish characters for their queerness or promiscuity, rather than dramatize the horrible randomness of an epidemic compounded by the bigotry and willful ignorance of straight society. For more sympathetic writers, the temptation is to elevate the men who were lost during those early years into angels or martyrs or saints. Davies does something better. He insists that they shouldn’t have had to be monks to survive into middle age—and he directs righteous, well-deserved anger at the adults, in Britain and beyond, who raised their children to live in shame."

- Russell T Davies somehow manages to capture the shock of AIDS’ arrival in the early '80s: "The first death by 'gay cancer' is criss-crossed with the main characters being asked about their near- and long-term plans for the future — a juxtaposition that only works so well because series director Peter Hoar and editor Sarah Brewerton are faultless in their cutting rhythms," says Inkoo Kang. "A joyful early montage of Ritchie’s many, many club hookups — set to a medley of classical tunes — helps explain the life-affirming hedonism of promiscuity, even with everything that’s to come. And a later direct-to-camera address by Ritchie in 1983 about why he doesn’t believe that AIDS is real — 'they wanna scare us and stop us having sex and make us really boring' — elucidates how legitimate anxieties about homophobic persecution, combined with the mixed messages that arise from scientific uncertainty, made the revelation of a new virus difficult to accept."

- It's a Sin is really a historical horror show: "HBO Max’s It’s a Sin runs through vibes and genres like a DJ running through songs," says Brett White. "Comedy, drama, coming-of-age, romance, ’80s nostalgia-fest—the show does it all and it does it all well. Showrunner Russell T. Davies crafted a cast of charismatic, immensely lovable up-and-comers playing characters that feel so real because they make you laugh and cry. And the show’s place in the queer canon is cemented the instant Roscoe (Omari Douglas) not-so-politely tells his family what they can do with their bigotry. It’s a serve, and sure to become a staple of queer memes and drag culture. But of all the genres that It’s a Sin does (and does well!), there’s one genre that holds it all together and makes It’s a Sin not just an entertaining watch, but a required watch: It’s a Sin is a horror show, and it’s made all the scarier because the horrors were—and remain—real."

- It's a Sin is heartbreaking, propulsive, galvanizing and even joyous: "This is a stirring requiem for the dead, shot through with defiant life," says James Poniewozik, adding: "Part of this moving and excellent series’s power comes from how brutally it lays out the story we know is inexorably coming. But the greater part is in how it also shows us the stories that these young men should have had, the stories that they were robbed of, the stories that society and fate allowed generations of straight men before them."

- It’s a Sin has a crystalline sense of the power of its project: "But it makes room, throughout, for small moments of grace. Its characters are not saints or martyrs but people who lived — making death, when it enters the story, feel all the more real," says Daniel D'Addario, adding: "It shouldn’t be a surprise that there’s little uplift to be found here, in the traditional sense. But the warmth of fellow-feeling took me aback; characters understand and forgive one another’s vulnerability and — in Ritchie’s case — their errors in judgment when it comes to how they treat their fellow man. Despite the audience’s knowledge that the 1980s are a bad decade that gets worse and worse for gay men, the series doesn’t get ahead of its own characters; it doesn’t judge them, either, even as it appraises them clearly."

- It's a Sin was particularly groundbreaking when it aired in Britain as the country's first TV series to directly grapple with the AIDS crisis: "This immediate reaction to It’s a Sin, which has now become available abroad via HBO Max, has lingered on my mind," says Alistair Ryder. "For a show that comprehends the weight of the AIDS crisis and its impact on a group of friends over the course of a decade, why was the gut instinct to center the imagined response of younger closeted viewers? The answer to this question goes some way to explain why the show has been so groundbreaking in its home country, in a way that may get overlooked by international viewers; that nearly 40 years later, this is the first time a TV series had directly grappled with how the AIDS crisis devastated Britain’s gay community. A 'culture of silence,' like the one depicted in the show, has only continued to persist, and that this series exists in any form is something approaching a miracle. But more importantly, it’s a tribute to a lost generation of gay men, that presents their lives as more than just the sum of the tragedies inflicted upon them. There’s a refreshing boldness to a show about the gay community during this era that is so sex positive, removing the shame and stigma around their sex lives to tackle the bigger issues around how these men were unfairly treated by society. The history of AIDS remains under-discussed in the UK education system (if mentioned at all), so what better history lesson for younger gays than a show that wouldn’t dream of demonizing them, or attempt to scare them off sex altogether?"

- It's a Sin has one big blind spot: "Black characters and other characters of color should also have the right to die tragically in sweet, poignant stories about nightmarish moments in history," says Kathryn VanArendonk. "That’s a slightly off-center place to begin a review of Russell T Davies’s often beautifully moving limited series It’s a Sin, about the AIDS epidemic in London. But the series follows several young people throughout the 1980s and early ’90s as they experience the horrific toll of HIV and AIDS in the gay community, and one of the show’s foundational ideas is that the marginalization and shame of queer communities is key to what made the AIDS epidemic so devastating...For many of the main characters, It’s a Sin is a really wrenching, beautiful exploration of that idea, and the series begins with a kaleidoscopic, ensemble approach to its story. There’s closeted Ritchie, who moves to London from his small town on an island off the coast of England; there’s bashful Colin (Callum Scott Howells), who gets his first job in a fancy menswear store; and there’s Roscoe (Omari Douglas), who leaves home after his family tries to convert him with prayer and community shaming. They all eventually become friends with Jill, and especially in the first episode, there’s a sense that these stories will be three interwoven threads with relatively equal weight throughout the series. Ritchie and Colin are white; Roscoe and Jill are Black. To fully explain the show’s preferences, its priorities in what kinds of characters get to be heroic martyrs and what characters watch sadly from the sidelines, I’d have to spoil it, to lay out exactly who dies and when and how. I’m not going to do that. In spite of my frustrations with the series, It’s a Sin is very much worth watching."

- Davies takes an honest look at the physical toll of the AIDS epidemic: "He depicts how society moved too slowly to stop the spread, while ignoring (or condemning) its victims," says Darren Franich. "But he also uses the miniseries format to evoke far-flung layers of experience. In the stunning conclusion of the first episode, Roscoe, Ritchie, and Colin reveal their dreams for the future. That montage full of hope cuts to a lonely AIDS victim dead in an empty hospital wing. Nurses appear and wipe his space clean: an act of erasure, and a bed too many other men will fill."

- Russell T Davies wanted to write It's a Sin based on the memories of his friends who died of AIDS and those who survived: “That’s how I remember those people,” he says. “I think many of those lives that ended too soon have been remembered with a lot of stigma, a lot of shame and embarrassment, and with a respectful silence over them. But I just wanted to show them living their lives and having a great time.” Davies had been thinking It's a Sin since 1995, four years before he made Queer as Folk, which was actually criticized for not addressing the AIDS epidemic. But it didn't start taking shape until 2015. It's a Sin was originally titled The Boys, but Davies came up with a new title in response to Amazon's superhero series of the same name. "And thank god ... it’s a much better title!" he says.

- Davies was taken aback by the straight audience's reaction to It's a Sin in Britain: Davies says he's somebody who is "quite television-literate. I can predict most responses to something. And what I hadn't realized is that I live in a very gay world and the media is a very gay-friendly world. If you go to a charity event, it'll probably be an HIV event. And my magazines and my plays... I'll go and see Angels in America. My culture is full of this stuff, and you forget what a bubble you're in. Actually, the reaction to this from a straight audience has been phenomenal. Children and young viewers, especially, are absolutely shocked at what they're seeing, which I hadn't predicted. If you'd asked me at Christmas, when I was planning the launch of this in January — you're excited about launching a new show, but you're also dreading it at the same time in case it dies a death. I was literally going to bed thinking, God, I think I pulled my punches on the show. I don't think it's strong enough. I think I've held back a bit. I know, because I did try to keep the temperature under control, keep the anger under control, because I wanted it to be not fueled by anger, I wanted it to be a more accessible and more open show, to find different things to say other than anger. I was really thinking, Gosh, I haven't quite landed this because it's not quite shocking enough."

- From Queer as Folk to Doctor Who to Torchwood to Cucumber: A guide to Russell T. Davies' queer canon

- Watch the first episode of It's a Sin posted to HBO Max's YouTube channel

TOPICS: It's a Sin, Channel 4, HBO Max, Russell T Davies, LGBTQ

More It's a Sin on Primetimer:- Neil Patrick Harris Joins Doctor Who In Mystery Role

- Insecure, Dopesick and Reservation Dogs are among the winners of Television Academy Honors Award for inspiring social change

- GLAAD Media Awards honor Hacks, Saved by the Bell, It's a Sin, We're Here and RuPaul's Drag Race

- Handicapping the Critics' Choice TV Awards